Update: There is a little bit of background static and a couple of hiccups in this recording, but I think this is an improvement over simkl (which sped up my voice) and Pamela (which echoed). I am now using VodBurner. Sorry to take awhile to post this. I had to fix some problems with Skype, but hopefully this audio is better. Thanks so much to Brandon for staying up late last night and chatting with me on Skype to help me with my technical problems! My dad and I will be doing another update around lunchtime EDT today. The interview below was conducted around 7pm EDT on Thursday, March 17th.

Here is the 7th interview I have conducted with my dad, a nuclear engineer. Please see the rest of the blog (sidebar) for previous interviews.

Please keep sending questions and comments to georneysblog@gmail.com. You can also follow me on twitter @GeoEvelyn but please do not send questions via twitter.

Here is the audio file:

Here is the vimeo video:

information going around, we should do an evening call. Before we begin, let me

just say that my name is Evelyn Mervine, and I am interviewing my dad, Mark

Mervine, who is a nuclear engineer. This is the 7th in a series of interviews that

I’m doing with my father, about the Fukushima nuclear power plant disaster in

Japan. And I’m just gonna make a couple comments, first I really want to think a PR

representative from Skype, who is trying to provide me with support for clearing

up the call quality and some of the issues that we’ve been having with that. He said

he’ll continue to support me on trying new software, hopefully there are fewer

problems with this one. And my dad says if I don’t get my act together soon, that

he might replace me, so I really need to get going on the call quality. And I also

really want to thank all the people who have been transcribing the interviews, in

particular, Michelle, who has done several of these transcriptions. If you’d like to

help out with transcribing as well, maybe give Michelle a break, send an email or

just post a comment and let me know, thank you very much.

With that said, Dad, could you please give us an update about what’s going on

in Japan?

A: OK, there’s been a lot of activity today. And, just as a reminder for everybody,

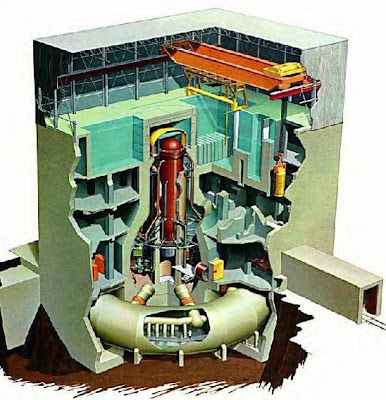

at the Fukushima 1 nuclear power plant, there are actually 6 reactors. 3 of which

were operating at the time of the earthquake and 3 which were shut down for

maintenance. The 3 that were operating were Units 1, 2 and 3 and Units 4, 5 and 6

were shut down. So we’ve mainly talked about Units 1 through 4 because those are

the ones that have been the biggest concern. And I think it was yesterday, I talked a

little bit about Units 5 and 6. So although these plants are all in the same area, Units

1 through 4 are very close to each other, and Units 5 and 6 are very close to each

other. But there’s quite a distance between Units 1 through 4 and Units 5 and 6.

Units 5 and 6 were also affected in that they lost power, but they were able to

regain one of the diesel generators at Unit 6. When we talked before, we said that

they were trying to run the equivalent of a long extension cable from the diesel

generator at Unit 6, over to Unit 5, to get some power over there. And I’m happy to

report that they’ve been successful in doing that. And so now we have some power

at both Unit 5 and Unit 6. And with that power, they hope to be able to pump

enough water to keep the reactors and the spent fuel pools in those two units

covered and safe. So that’s quite a bit of good news.

Q: Can I ask a quick question, Dad, maybe you can comment on this. Are some of

the workers that are doing this work, are they really risking their own health doing

this? Are there people really going in there – I know that they’ve reduced the staff,

but clearly, there’s still some people working in the vicinity of the power plant?

A: So most of the problems are coming from Units 1, 2, 3 and 4. And because

there are a fair amount of separation between those and Units 5 and 6, I think

anybody working over at 5 and 6, it’s probably a little bit better off. Because the

way radiation works is the farther you get away from it, the more it attenuates and

the lower the dose will be. So we always used to say in the business, in dealing with

radiation, it’s Time, Distance and Shielding. So it’s how much time you spend in the

radiation field, it’s how close or how far away you are, and it’s how much shielding

you have. So it’s very good for those two units, they have some physical separation,

which means the radiation levels will be lower over at those units and I think that

that’s why they’ve been able to be more successful in getting a diesel generator

running, maybe it was less damage, but in any event, very good news to have some

power to both of those units.

I think the other good news is with respect to the reactors in Units 1, 2 and 3.

They’ve been pretty stable today. They’re continuing to pump in seawater, they’re

continuing to periodically vent to keep the pressure down, to allow the seawater to

flow in. They still don’t have the cores completely covered in those three reactors,

but the situation is not getting any worse. It’s at least stable.

Q: And there are people- I guess the radiation levels, other than at that one pool,

which you can mention again, that’s having trouble – people are actually able to get

in there and do things like release steam and monitor the pumps. There are actually

workers in there?

A: So I don’t have any details on the actual radiation levels within the plant. But

I think it would be safe to say that the radiation levels are elevated, due to the fact

that we know that there’s been damage to the fuel in all three of those reactors.

Q: So if there are people working in those – obviously we don’t have information

about the radiation levels, but their health risk is higher, and those people- I mean

in my opinion, if there are people in there working, they really are heroes, to go in

there and to try and get things under control there. At risk of radiation, so OK, go

ahead, Dad, sorry.

A: So we don’t know exactly what the radiation levels are, but we know 48 hours

ago, they had to temporarily evacuate the plant, because the radiation levels had

spiked. We know that the helicopters can only fly so low because of the concern

for the radiation coming from some of those units. So we know there are definitely

places where the radiation is very high and definitely we have people that are

risking their lives to try to bring the situation under control and keep all of us safe.

In any event, let me continue with the status. So the water level and

condition units of 1, 2 and 3 are stable, compared to yesterday. They’re certainly

not where we like them to be, the cores are not completely covered, but the

situation has not gotten any worse in the 24 hours. And I think that’s important,

because up until now, it seemed like the situation was getting worse. Today, we

have improvements – we’re stable in 5 and 6, we have some power to both of those

plants, we have stable water levels in 1, 2 and 3. We don’t worry about Unit 4

reactor because all of the fuel was removed from that one. What we do have

concerns about, obviously, is the spent fuel pools. And the ones that have been of

the most concern have been Unit 3 and Unit 4 spent fuel pools. And we had

reported that the NRC- the United States NRC – has stated that they believe that all

of the water was gone from the Unit 4 spent fuel pool. So there’s some good news

and there’s some bad news, with respect to that pool. The good news is they we

able to see by camera today, that there is still some water in that pool. The bad

news is the side of that pool, the concrete side of it, has collapsed. Fortunately, the

pool has a steel liner, and the steel liner is intact. But that’s obviously a very close

call, to have basically that huge section of concrete, to have collapsed around that

pool. But the good news is that there’s still some water in there and today, they did

two things – they dropped water from helicopters, which was, from the photos

looked to be fairly ineffective, in that because they have to fly so high, most of the

water was carried away by the wind. But they also used those water cannons we

talked about to shoot water into both Units 3 and 4. And when they determined

there was still water in the Unit 4 pool, they turned more of their attention to Unit 3.

Some other good news is they completed running a cable from the electric

power grid over to Unit 2. And according to news reports, they were waiting to

finish spraying water on Unit 3 before they made the final connection on that cable.

And that would allow us to get electric power from the grid to Unit 2.

Q: Only to Unit 2? Now that the electricity has come so far, will it now be quicker to

restore electricity to the other ones or is it only going to be for Unit 2?

A: Well, that was going to be what I was going to say is hopefully that they’ll also

be able to restore electrical power to Units 1, 3 and 4 as well in the next day or so.

So I think it’s very good news because the reason why it’s taken so long is because

of the damage from the quake and the tsunami, they had to rebuild the electric

transmission lines to the plant and then run these news cables over to these reactor

units. So the fact that they’re making this much progress, I think, is a very good sign

and I hope maybe by the morning update, we’ll be able to report that they’ve been

successful – or very close to successful – to getting some power back in Unit 2.

One they get power back to these units, then hopefully, they’ll be able to

work to restore some of the normal and backup pumping systems, to pump water

into the reactor vessels and the spent fuel pools.

Q: Just quickly Dad, and I forgot to do this earlier and I have been trying to do this

at the beginning of the interviews. Today is March 17th and it is currently 7 PM,

Eastern Daylight time.

A: OK. So that’s the update. Like I said, quite a bit of activity, quite a bit of news

from this morning and I wanted to take a few minutes and give people that update.

Hopefully, maybe this evening on the news, there will be even more information, but

that’s the update that I have as of 7 o’clock, Eastern Daylight Time.

Q: The other thing is that we’re going to continue doing these, the daily updates as

necessary, for a couple more days, until things get under control, but we’re really

hoping that the situation stabilizes there. And the other thing that we mentioned

this morning is that we really do think the media is starting to do a better job about

communicating things. Can you expand on that?

A: They’re doing a better job. The one thing that I pointed out in one of our

interviews, and I’d like to point out again, because I see the same comment being

made over and over again – that we should be more concerned about the Unit 3 pool

than any of the others, because of the fact that that unit had mix oxide fuel. And we

explained what that was. That’s a fuel that has a mixture of both Plutonium and

Uranium and the concern is that since the Plutonium is more harmful to humans,

that that is a more significant risk. But as I explained, all reactor fuel that’s been in

the reactor for a period of time has Plutonium in it, because reactor fuel is normally

96% or 97% – the percentage will vary a little bit, depending on the design of the

core and the where that bundle is placed in the core, but approximately 96% of

Uranium-238 and 4% Uranium-235. And only the 235 can be used for reactor

fuel. But what happens in a reactor is the Uranium-238 will absorb a neutron and

become Uranium-239, and then after a couple of decays, it will become Plutonium-

239. And Plutonium will fission and, just like Uranium-235, it’ll release energy. And

so in fact, when a commercial reactor’s operating, a good percentage of the power,

it comes from the fissioning of Plutonium. And any fuel rod that’s been in a reactor

for any period of time, it’s gonna have a significant quantity of Plutonium built up in

it. It may be true that the fuel rods in Unit 3 that had the MOX fuel in it has a higher

percentage of Plutonium, but the point is, all fuel rods that have been in a reactor

have Plutonium. The other thing, I think, to point out is – and the reports that I saw

said that they have only been using that mix oxide fuel since last October. So not the

entire core contains mix oxide fuel, only about a third of it, which would’ve occurred

at the refueling, which apparently they did last October. So I just wanted to clarify

that, a lot has been made in the media of that and I’m just kinda surprised that none

of the commentators and the nuclear experts that they’ve brought in – either on the

news or on the written media – have corrected that point, or made that clarification.

That, in my opinion, there may be slightly more concern about Unit 3, but in reality,

all of that fuel has Plutonium in it and I would consider it all dangerous.

Q: Can you just clarify again, so not all of the pools are in trouble? It’s just pool 3

and pool 4, is that correct?

A: Well, we don’t have the information. As we commented before, we need

the Tokyo Electric Power Company to be more transparent. We don’t have any

information on the spent fuel pools at Units 1 or 2 or the shared one, I think I

explained this morning, there’s actually 7- there’s 6 reactors, but there’s 7 fuel

pools. There’s one in each reactor and there’s a common one. And we’ve only been

provided information on 5 and 6 and then we were provided information on 3 and

4, not because they provided information, but because they became problematic

and started to boil off. And we believe that enough had boiled off on Unit 4 that

hydrogen was formed, which caused the hydrogen explosion. It couldn’t have come

from the reactor because the reactor didn’t have any fuel in it. So they still need to

be more forthcoming and provide more comprehensive information. I would hope

that if conditions allow, that they continue to monitor and check on the spent fuel

pools in Unit 1 and 2, so that they don’t become problematic as well.

Q: So how many explosions have there been now? There’s been so many, I can’t

keep track, have there been 4 major explosions?

A: To my knowledge, there have been 4 explosions. In reactors 1, 2 and 3, it

was caused by the venting of the reactor vessel, in order to lower pressure. We

explained how if the fuel had gotten too hot, it would- the cladding of the zirconium

would interact with water to form zirconium dioxide and hydrogen. And when they

vented steam in the reactor, to reduce pressure to allow the seawater to be pumped

in, they were venting steam plus some radiation particles plus hydrogen, and

apparently there was enough hydrogen that when they vented that into the reactor

building, there was an explosive combination and when that hydrogen mixed with

the oxygen in the air, it exploded. The only possible explanation for the explosion in

Unit 4 would’ve been that hydrogen coming from fuel in the spent fuel pool, because

the reactor itself had had all the fuel removed.

Q: Can you comment on something that you just mentioned to me in a private call,

about the concern that you have about the radioactivity of the water that they’re

using now?

A: I’m sorry, what’s that?

Q: You were mentioning to me that normally, the water systems in the spent fuel

pools, it’s a recycled system, and it goes through piping and normally that water has

a relatively low level of radio activity, but now you’re concerned that that level has

increased?

A: So normally in order to keep the reactor cool when it’s shut down and the spent

fuel pools cool, water is pumped from them through a heat exchanger, and cooled by

a cooler water. It could be the ocean water, or maybe a second closed loop, but any

event, through a heat exchanger, which cools it, and brings it back into either the

reactor or – in the case of the spent fuel pool, back into the spent fuel pool. And

since we have had fuel damage in the reactors – let’s take example of Reactor 2. If

they’re able to get power back to that reactor, and if we can get the pumps working,

we’re gonna take water from the reactor, put it through heat exchangers, put it back

in the reactor. And normally, that water going into those pipes would only be

slightly radioactive. But because we’ve had the fuel damage, and we’ve had the

release of the radionuculides from the fuel, the radiation levels, as the water flows

through those pipes, around those pipes will be much, much higher than normal. So

we’re kinda getting ahead of ourselves, in terms of them being able to restore the

plant. But if they were able to restore cooling, they would have to be concerned for

people working the vicinity of that piping and pumps, because the radiation levels

would be much, much higher than normal. But again, we’re a little bit ahead of

ourselves. They first need to get power back and hopefully, they’ll be able to get

some pumps back and initially, they won’t be circulating the water, they’ll be

pumping in as much as possible to get everything back up. Once they have

everything back up, then they’ll have the consideration for now reforming that

closed loop and cooling the water. And they’ll have to be careful because the

radiation levels will be much higher in those areas.

And that would not be a concern to anybody off-site, that wouldn’t only be a

concern right there, at the plant. I mean, it would be very, very good news if they

got the power back, to get the reactor vessel and the pool- fuel pools filled back up

and be in a situation where we now could restore some of the normal shut down

cooling systems. We’re not there yet, we’re probably a long way from there, so…

The only other thing that I would like to point out is yesterday, the radiation

levels at the site boundary were quite high. Again, it’s difficult to piece all the

information together, but the news report that I saw said they were between-

somewhere between 30 and 40 millirem per hour. Today, they reported as being

between 2 and 3 millirem per hour. So to me, that means that some of the work

that’s being done in the 24 hours has been effective. Even though it didn’t look

like we got a lot of water on those pools from the helicopters. Hopefully, the

combination of helicopters and water cannons were effective in getting a little more

water in those pools, which apparently has knocked down the radiation levels.

And that’s very, very good news. 2 to 3 millrem per hour is certainly well-above

normal – it should normally be barely detectable, but those are quite tolerable

levels. Now obviously as you get closer to the actual damaged power plant, those

radiation levels are going to go up. But the fact that those went down by a factor of

10 hopefully means that also, within the plant, the radiation levels have dropped

substantially. Maybe not by a factor of 10, but maybe at least a factor of 2.

Q: That’s very good news. So I’m gonna ask this question, and I know I keep asking,

but the situation keeps changing. I know this morning, you had mentioned that the

US was preparing to evacuate US citizens, just in case. Do you recommend at this

point, that US citizens, if they can, if they have any means, should they try and leave

Japan still or do you think that this situation is stabilizing?

A: Well, I’m not in the position of making a recommendation as to what people

should do. I’ll go back and- because I don’t have the information. The Japanese

government has an order in for people to evacuate up to 30 kilometers. The US

government yesterday made a recommendation that people should evacuate for a

distance of 50 miles, or approximately 80 kilometers. And they based that

information on the information that they had, and they believed that there was

absolutely no water in the number 4 reactor spent fuel pool. Photographic evidence

today indicates that there is still water in there, so maybe that was a bit of a over-

estimate on the part of the NRC, but as we discussed this morning, part of the

problem has been the lack of information and I- there may be people that point to

our government and say that we did an overreaction, but the purpose of the

government is to protect its people. And they made, I’m sure, what they felt was the

best recommendation, based on the information that they had or based on the fact

that they didn’t have information. We also know that they’ve recommended people

to evacuate- Americans evacuate from Japan – and they’re offering flights to

evacuate. But as we talked about this morning, the radiation levels, outside of that

immediate plant area- I should say outside of the 30 kilometer zone, have not been

high enough to cause concern from a human health perspective. And certainly the

levels in Tokyo, although there has been some elevated levels, are not to the point

where any kind of evacuation or panic should be taking place. And the biggest

concern and panic, I think, was just coming from the fact that there’s no

information. But in terms with the recommendation, my advice is follow the

recommendation of the government. If you’re an American citizen and where

you’re at, the government is recommending that you move out of that area or

evacuate, then I would follow that advice and if you’re a Japanese citizen, I would

follow the advice of your government. And I’m just gonna leave it at that, because I

don’t have access to that information.

Q: Thanks very much. And again, just to point out, there’s not an immediate risk in

the United States, there’s still many people panicking about possible radioactivity

being in the US, but-

A: I’ve only heard a small portion, because I was driving, but the president made a

statement today and he said what we said this morning, which is the- there is no risk

right now, unless the situation becomes a lot worse, to anybody in the United States

of America. There’s no reason to be concerned, there’s no reason to panic, there’s

not reason to be hoarding batches of iodide pills, there’s no reason for any of that.

We’re 5 thousand miles away and there’s absolutely no concern whatsoever.

Q: I’m glad that we can echo our president and I’m glad that that information is

getting out there to the American people from a source that I’m sure has many

more listeners than we do. So I’m just gonna end- we’re actually just gonna ask

one question tonight, and I’ve been receiving many questions and many emails and

I want to thank you for those emails, they do mean a lot to my dad and I, there’s a

lot of people who’ve been saying thank you and we really appreciate those emails,

and keep sending them. We have been receiving a lot of questions. Many of those

questions we’ve received we already answered, so if we don’t answer your question,

maybe check some of the previous recordings and transcripts, we’re not gonna

duplicate questions and we can’t answer every question, so we apologize if we don’t

answer your question. The one that I wanna to address tonight is a question that

came in from a few different listeners. And they wanted to know about shielding,

because I guess people always think that things like lead and concrete can shield

radioactivity. And they wanted to know why you couldn’t just go pour concrete over

things to keep the radioactivity from affecting humans?

A: OK, well, that’s a good question. And the problem that we have right now is the

radiation levels around the damaged plants have been quite high and anybody that’s

had a chance to watch the pictures on TV of the helicopter dropping the water could

see that they’re having to fly fairly high, which if they could fly a little bit lower, they

would’ve been able to be a little more accurate with the water drop and the wind

would’ve carried less of it away. But they were flying the height that they were in

order to protect themselves from the radiation that were coming from those plants.

And the reason why they brought in water cannons, instead of normal fire trucks is

because of the power of the water cannons and the ability of them to shoot the

water farther, so they could be father away from the plant. And again, for the same

reason, the radiation levels around the plant were really too high for them to get any

closer. Again, it’s time, distance and shielding. You want to minimize the time

you’re exposed to radiation, you want to maximize the shielding and maximize the

distance. So the question about shielding is a really good suggestion. The problem

you’d have is, in the case – say if somebody wanted to say, “why don’t we put up

some lead or whatever?” Lead is very heavy and you would need heavy equipment

to move it, and you would have to get very close, and so that would be a problem

right now. The same problem would be to pour concrete. In order to pour concrete,

we’d have to put up some forms and usually installing forms is a fairly manual

process, and then you’d pour the concrete and then you remove the forms. We just

wouldn’t be able to get close enough right now to be able to do anything like that.

The best solution is water. If we can refill those pools, which are apparently intact.

The side of Unit 4 pool is damaged, the concrete has fallen away, but the steel liner

is still in place and that should still- it is holding water. So our best solution is to

refill those pools and water is the other really good radiation shield. And if we can

refill those pools, the radiation levels will certainly be higher than they normally

are, because of the damage to the fuel, but the water will do an excellent job

attenuating that radiation and bringing the radiation levels down. And then,

depending on the long-term situation of the plant, and what they’re able to do and

how much the damage was, it would become necessary to do any type of radiation

shielding construction, they would be in a better position to do that because the

water would be attenuating a lot of the radiation and the dose rates would be much

lower, which would allow people to do two things – get closer and also spend more

time in close proximity to the plant.

So, I think those are really longer-term solutions and not solutions that could

be put in place in the short-term. And that would be- y’know, you asked the

question about water flowing through the pipes, once we’re able to get cooling

restored. Those are the type of things that they would do in the areas of the plant

where the water’s flowing, but the radiation levels are maybe very high. They

would bring in some additional lead shielding or some additional concrete blocks in

order to attenuate that radiation and allow people to get a little bit closer to that

area.

Q: Just to clarify a point that maybe I’m a little bit confused on, so even though I

know you’ve explained this before. It’s important to add not just water, but water

plus boron, is that right? I mean, if you just pour plain water on it, that is not

necessarily the best thing to do, is that right?

A: So normally, you would not have to add Boron, you would just be able to add

water. But what we explained- and again, this is starting to run together, we’ve

done so many interviews – I think we explained it this morning, but- ‘cause there

was a question about would the fuel pool achieve criticality. The- in the reactor and

in the spent fuel pool, the geometry is really important. So in the spent fuel pool,

the rods are- the spent rods are kept- and actually in this type of plan, it would be a

fuel assembly – are kept separated at specific distances in a grid pattern. And that

spacing is important because we don’t want to have enough neutrons to actually

cause any type of fission or reaction. We want everything to be, what’s called “sub-

critical”. The same in a shutdown reactor, we insert the control rods and the

control rods in this type of reactor go up in a cross-shape fashion, in between 4

fuel bundles. And they absorb the neutron and shut down the self-sustaining chain

reaction. What can happen when the fuel is damaged – and we don’t know the

extent of the damage, because we’re not able to get inside the reactors, of course,

and we’re not able to get to the spent fuel pools at this point in the game, to see the

actual condition of the fuel. But if it’s very damaged, it could be losing its shape,

it could be melting, essentially. And when you melt, you could lose the geometry

and therefore, they haven’t just been adding water, they’ve been adding water with

boron. Boron is a good absorber of neutrons and all that is to make sure that if you

have lost geometry of the fuel, in either the spent fuel pool or the reactors, that the

boron would absorb the neutrons and prevent a self-sustaining chain reaction, or

criticality.

Q: OK, I think that that’s all for this evening. And we plan another update around

lunchtime, maybe early afternoon tomorrow. And as I’ve said, we’ll continue to do

these updates on a regular basis as the information comes in, as there’s something

important to discuss. And hopefully, it sounds like they’re getting the situation

under control now, so hopefully in a few days, we will be able to- we won’t have

to do as many of these, certainly not every day. And I know that, Dad, you have a

business trip coming up, so in a few days, we probably won’t be able to do these

anyway. But we will continue, even after this, to try and update you on a regular

basis, we might just switch to every few days instead of every day.

A: The only comment that I would add is in the case of most of these types of

things, as long as there is something happening and it’s fairly sensational, it gets a

lot of attention in the news. The situation we have at the plants is something that

hopefully in the next few days, can be brought under control. But there will be many

days, many weeks, many months of work ahead to completely stabilize and restore

power and cooling at these plants. So probably long after the cameras and the news

crews are gone, there will still be a lot of work and a lot of concern going on at these

plants. And the only reason I say that is I don’t want everybody to think, oh, they’re

gonna get power back tomorrow and then everything’s gonna be OK. They’re going

to get power back and that’s going to improve the situation. And then hopefully

they can get some higher-pressure pumps and completely fill those reactor vessels.

But because of the radiation levels, because of the difficult working environments,

because of the damage to the plant from the explosions, from the tsunami, there’s

probably many days, many weeks of work ahead before they’re able to restore

enough systems to actually be completely bring the situation at these plants under

control.