I am a geochemist. For my PhD thesis, undergraduate, and summer internship research, I have spent thousands of hours in geochemistry labs. I enjoy labwork, and I take laboratory safety seriously. When I work in the laboratory, I usually wear an outfit similar to the above. In the above photograph I am wearing an acid-resistant lab coat, long pants, closed-toed plastic lab clogs (out of the picture, but believe me), gloves, safety glasses, and a hair net to keep my long hair out of my way (and also out of my samples). As much as possible, I keep the chemicals I work with inside fume hoods, which protect me from dangerous acid vapors. When I work with especially dangerous chemicals such as hydrofluoric acid or aqua regia, I usually add a full face shield, an extra pair of gloves, and sometimes an extra labcoat or apron to the above outfit. In some labs I wear a full tyvek jumpsuit rather than a labcoat so that my legs are better protected.

The clothes I wear in geochemistry labs may not always be the most flattering (although, personally, I think I look pretty good in a labcoat), but that’s not the point. The point of these clothes is to protect me from dangerous chemicals. Everyone dresses like this in geochemistry labs (or should), and no one worries over fashion when donning laboratory gear. Why? Because looking fashionable is not particularly important when you are trying to prevent acid exposure. Preventing acid exposure can literally be a matter of life-and-death. Unfortunately, rocks (especially silicate rocks) do not like to dissolve. So, geochemists use a very dangerous acid called hydrofluoric acid to bring them into solution for chemical analysis. Exposure to hydrofluoric acid is initially painless (because it interferes with nerve function), so you often don’t know that you’ve been exposed until hours later, when your flesh and bones have started to dissolve. A large hydrofluoric acid exposure is lethal, so I always, always, always wear my protective laboratory gear when working with hydrofluoric acid and also when working with other, slightly less dangerous acids.

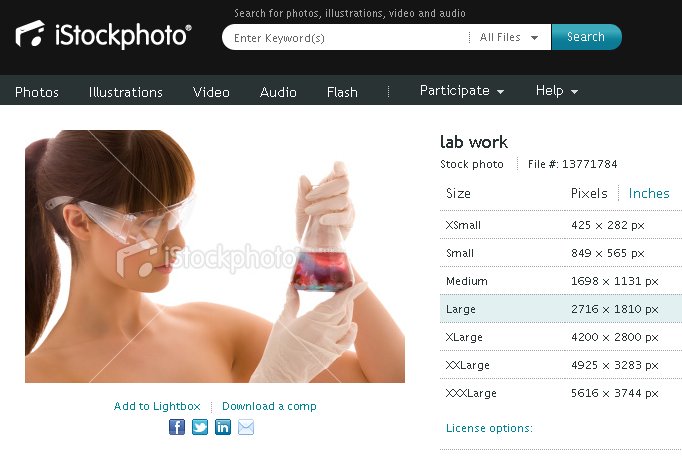

You might be wondering why I’m posting the above photograph and explaining how geochemists generally dress. I am posting this photograph because there has been a disturbing stock photograph titled “lab work” that has been circulating around the science blogosphere recently. Here is the picture:

In the above photograph the female chemist is either (1.) naked or (2.) wearing a strapless top or dress. Neither type of attire (or lack thereof) is appropriate for chemistry. There is far too much skin that could be exposed to dangerous acids. Furthermore, if that beaker contains acid, the chemist really should be handling that beaker under a fume hood. Perhaps that is the problem– maybe the acid fumes have dissolved her clothes? In that case, she really should consider wearing a more acid resistant tyvek suit or coat.

Joking aside, the stock photograph really disturbs me. Is this how we want the general public to view lab work? Why does the female chemist look naked? Is it to make her more attractive? Why is it important for her to look attractive? I suppose that I understand that stock photos usually feature more-attractive-than-average people, but does she have to look naked to look attractive?

Even Barbie, who is definitely a fashionista, is smart enough to wear proper laboratory safety clothing when doing geochemistry:

Geochemist Barbie and I are appalled at the stock photo of the naked female chemist. I really hope that not too many people actually purchase this stock photo. Rather than use that stock photo, I encourage you to– please– rather use a photograph of a real scientist dressed in real laboratory safety gear. If you’re considering purchasing that stock photo, you’re more than welcome to rather take the picture of me (for free!) or of Geochemist Barbie (also free!) in our more realistic laboratory clothing instead. Also, I have a proposal for other chemists: why not post pictures of you in your laboratory clothing, as I have posted here? If you don’t have a blog, I’d be happy to host your picture here at Georneys. I’ve been really impressed with the recent This is What a Scientist Looks Like effort, which was initiated by Allie Wilkinson. Why not start a similar effort, perhaps titled “This is What a Chemist Looks Like” or “This is What Lab Work Looks Like” ?