Category: Uncategorized

A Quick Note: Upcoming Interviews with My Dad, a Nuclear Engineer, and Lulu Book

Some Quick Announcements:

1. Upcoming Interviews:

While my dad and I wish we could stop doing our interview updates, the situation at Fukushima remains serious. We will discuss this more in our interview tonight, but keep in mind that the nuclear disaster at Fukushima will not be resolved in a matter of days; there are many long months and years of work ahead, especially since some of the reactors have been badly damaged by the earthquake, flooding (from the tsunami), and subsequent explosions. To fully clean-up the Fukushima site will require decades.

We probably won’t continue doing these interviews for decades, but we will continue them awhile longer.

This week we will be conducting interviews on Monday (3/28, later this evening), Tuesday (3/29), and Friday (4/1). Please send any questions or comments to georneysblog@gmail.com. You can also follow me on twitter @GeoEvelyn.

2. Lulu Book:

I just wanted to let you know that sometime soon (sometime in April, hopefully) I plan to self-publish a book titled “Conversations with My Dad, a Nuclear Engineer, about the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant Disater in Japan” on Lulu. In this book, I will compile all of the interview transcripts (which I will clean-up and check for errors) and also write brief summaries of the content in each interview. I will also include a chapter with some background on my father and I, including some pictures of us over the years, and a chapter with some of the many, many emails and comments we have received in response to these interviews. For the emails and comments, I will only use first names (or anonymous if the person did not give a name) and will avoid any personal details.

My father and I will donate 25% of the profits of each book to charities supporting Japan earthquake and tsunami disaster relief. If you have any interest in buying a book, let me know in a comment below or by email so that I have a rough idea of how many books might be ordered.

The interviews and audio files will remain freely available here always; I just thought that some people might like to have all of the interviews compiled in an easier-to-read book form. As I mentioned, I will try to have the book published sometime in April; I have a long plane flight to South Africa coming up in a few weeks when I can work on this. Depending on the situation at Fukushima, we may continue to do these interviews on a regular basis for some time. So, it’s possible that the book will need to be updated at some point if we continue interviews past April.

3. More Thank-Yous

Thanks again to all of the transcribers and audio helpers. I mailed pretty rocks to the volunteer helpers below (except Gerald– send me your address if you want a rock) earlier today. Rocks are heavy, so I mailed them parcel post, but they should arrive sometime in the not-too-distant future.

-Skype PR Representative

-Michelle, Gregg, Kirsten, Sophie, Chris, & Maria (transcription)

-Brandon (vimeo & audio help)

-Mike (audio help)

-Brad (YouTube help)

-Gerald (audio file hosting)

13th Interview with My Dad, a Nuclear Engineer, about the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant Disaster in Japan

12th Interview with My Dad, a Nuclear Engineer, about the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant Disaster in Japan

Update: Sorry that it took me so long to post this interview, which was recorded last night. I had trouble converting the video file at first, but I think I’ve sorted it out now.

You can listen to all the interviews on the new vimeo channel Brandon and I created. You can also listen to most of the interviews on Brad Go’s YouTube channel.

Here’s the vimeo channel:

This evening my dad and I recorded our 12th interview on the Fukushima nuclear power plant disaster. Please see the rest of the blog (sidebar) for previous interviews. Please keep sending questions and comments to georneysblog@gmail.com. You can also follow me on twitter @GeoEvelyn but please do not send questions via twitter.

In today’s interview:

1. My dad gives his usual update

2. We discuss:

a) why salt might be a problem for nuclear reactors

b) Fukushima has dropped off the front page of the news, and the mainstream media is not doing the best job of reporting about Fukushima in recent days (on a soapbox again)

c) monitoring of radiation by the Japanese government and radiation in the environment

d) why reports about radiation levels need to be in units people can understand and need to be in consistent units

Hope to have an audio link soon. Here is the interview on vimeo:

Please see the announcement page for more information about these interviews:

If you have time and interest, please transcribe this interview. Our next interview will be on Saturday, March 26th. Thanks to Kenyon, a transcript is now available after the jump.

Transcript for Interview 12:

11th Interview with My Dad, a Nuclear Engineer, about the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant Disaster in Japan

10th Interview with My Dad, a Nuclear Engineer, about the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant Disaster in Japan

|

||

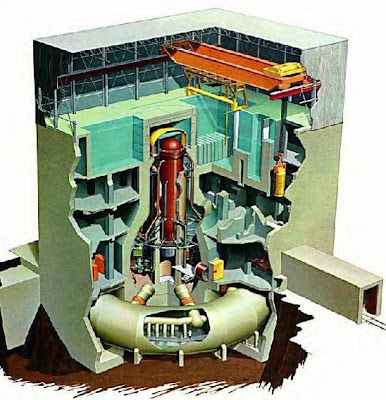

| Picture of a Boiling Water Reactor Nuclear Power Plant like the Fukushima Plants. My dad refers to this image in his interview. |

Update: Gerald has kindly hosted all of the new audio files. I will update all the audio links (some of which are broken) soon– I meant to do this yesterday or today but was overwhelmed with work. DONE Meanwhile, you can listen to all the audio files on the new vimeo channel Brandon and I created. You can also listen to most of the interviews on Brad Go’s YouTube channel.

Here’s the vimeo channel:

This evening my dad and I recorded our 10th interview on the Fukushima nuclear power plant disaster. Please see the rest of the blog (sidebar) for previous interviews. Please keep sending questions and comments to georneysblog@gmail.com. You can also follow me on twitter @GeoEvelyn but please do not send questions via twitter.

In today’s interview:

1. My dad gives his usual update

2. My dad and I step up on a soapbox and discuss: a) why nuclear organizations and the media need to be better about providing information about nuclear power and nuclear disasters, b) why the US should reprocess (recycle) nuclear fuel rods, c) long-term storage of nuclear fuel, and d) nuclear power, power plants in general, and the world’s energy needs

3. We address the questions “How do you move fuel rods?” and “Should the Vermont Yankee Nuclear Power Plant license have been renewed?”

Here are some websites we refer to in today’s interview:

Here is a statistic we discuss (from wikipedia, let me know if you have a better source):

Here is the audio file:

Hope to have an audio link soon. Here is the interview on vimeo:

Please see the announcement page for more information about these interviews:

If you have time and interest, please transcribe this interview. Our next interview will be on Thursday, March 24th. Thanks (again!) to Michelle, there is now a transcript after the jump.

Q: Good evening, Dad.

A: Good evening.

Q: Are you ready for our interview tonight?

A: I am.

Q: OK. Let me first say that my name is Evelyn Mervine and I’m gonna be

interviewing my dad, Mark Mervine, who’s a nuclear engineer. This is actually the

10th interview in a series of interviews that we’ve been doing about the Fukushima

nuclear power plant disaster in Japan. We’ve done interviews pretty much everyday

since the earthquake and tsunami. We’ve only missed a couple of days, we missed

yesterday because my dad was traveling and I had quite a bit of work on my

plate yesterday, and then also on Saturday, a few days ago, my dad was actually

interviewed by Anthony, who’s a Japanese citizen living in Japan, so other than

that, we’ve done these interviews everyday, but as I said, there wasn’t an interview

yesterday, so today we actually are going to do an update for the last 48 hours. And

then after my dad does his usual update, we’re gonna take some questions. And

since we’re doing many interviews, before we start, let me just say that today is the

22nd of March. And it is currently 9PM, Eastern Daylight Time. So with that, Dad, do

you want to give your update for today?

A: OK, so as a reminder to everybody, the Fukushima 1 nuclear power plant actually

consists of 6 reactors. We’ve been most concerned about Reactors 1 through 4.

And less concerned about Reactors 5 and 6. And there’s been a lot of activity in the

past 48 hours, but I will say that as I think is typical in most events, there’s a lot of

interest and information in the beginning, and then as time goes by, the press moves

on to something else and the amount of information gets a little harder to come by.

Now, maybe that isn’t the case within Japan, but it certainly is from North America.

So I’ll give the best update I can, based on the fact that information is getting a little

harder to come by.

Q: Is that mostly in the mainstream news? Are there still reports being released by

nuclear agencies in Japan and internationally?

A: There are, but the updates aren’t quite as frequent. Especially in the past couple

of days, there hasn’t been as many updates coming from Japan. But anyway, let me

give what I know. So probably the biggest news item is we now have power form

the grid to all 6 reactors.

A: Excellent.

Q: But that doesn’t mean that the pumps and the valves and the switch gear in those

reactors are powered up yet. They’ve just brought the power to those buildings, and

because of the damage from the earthquake and the tsunami and the explosions,

there’s still quite a bit of work to do within the buildings to get power restored,

so that you can actually use it. So the reports are a little bit hard to interpret, but

in Units 5 and 6, if people recall from previous updates, they had gotten 2 diesel

generators in Unit 6 started and were using power from Unit 6 to also power Unit

5, via the equivalent of a long extension cord. And based on what I could read, they

now have off-site power available to Units 5 and 6. Again, kinda the same way,

through the Unit 6 plant and then feeding over to Unit 5. But that’s very good news,

and also we had reported that a couple days ago that with the diesel generators,

they were able to restore the normal cooling systems to those plants and both of

those plants were in cold shutdown and clearly they have to continue to provide

power and cooling to them, but relatively speaking, they’re in a few safe condition.

The other thing we’ve talked about is the spent fuel pools at the site. There’s

actually 7 of them – one for each reactor building and then a common one. And the

reports are that the common pool is in good shape, that the temperature’s under

control and it’s not a concern. So let’s turn our attention to Units 1 through 4. So

we’ve brought an outside power to each of those units, but we haven’t actually been

able to power up pumps and valves and switch gear and that kind of stuff yet,

because of the extent of the damage. In the past 48 hours, a lot of attention has been

turned to the spent fuel pools at Units 2 through 4. And I would encourage people

to go to the International Atomic Agency website, which is – I believe – http://www.ie-

Q: IAEA, right?

A: Correct. Iaea.org [www.IAEA.org] . And they gave a very good summary today of

the status of the plant and the spent fuel pools. But in any event, the-

Q: So wait, someone’s doing our job now? That’s great!

A: Heh. Well, I’ve been using information gleaned from the NEI, from Wikipedia,

from news reports, from the IEAA- excuse me, International Atomic Agency to put

it all together so that we are able to give these updates. But they got a pretty good

overview there, which is worth taking a look at, and again, in the past 48 hours, a

lot of attention has been on spent fuel pools for Reactors 2, 3 and 4. And the fire

departments have pumped a lot of water on those. Now, today, they said they put

a fair amount of water on to the number 2 pool and cooled it way down. And since

that building is the most intact of all the buildings, I’m actually assuming that they

probably did that through a fire hose that they routed up through the inside of

building, as opposed to using the pumper trucks and the riot trucks that they had

used for the other builds. But in any event, they were able to put a lot of water in

that pool and cool it down, and if you want the specifics, I would encourage you to

go take a look at the website that we just mentioned.

There was some concern in the past 48 hours about Reactor number 3. It

had been reported that the pressure within the primary containment building had

gone up and they were considering whether or not they were going to have to do

some additional venting, but the pressure stabilized and they didn’t have to do that.

But then, yesterday, there was a bit of a scare in that there was some gray smoke

sighted coming from the vicinity of the spent fuel pool. And they actually evacuated

the site for a short period of time until they were able to verify radiation levels and

allow people to come back on site. I don’t think that they ever actually determined

what the cause of that was, but they continued to pour water- or shoot water at that

reactor building. So, go ahead, you gonna have a question?

Q: I was just going to ask, I know that in our last update, the radiation around,

I believe it was mostly spent fuel pool number 4 was so high that they weren’t

actually able to get very close, they were having to use these police water cannons.

Do you know, has the radiation level dropped? Are they able to actually get close

enough with fire trucks at fuel pool number 4 as well?

A: So in general, I think that the radiation levels were most elevated at Unit 3 and

4 and with these efforts that they’ve had to pour water onto these buildings, the

radiation levels have come down. They’re not great, but they’re better. But they’re

still requiring them to stay at some distance to be safe.

So the situation, from 48 hours ago, the situation is definitely improving.

They’re not making as much progress as I think we would all would like to fully

restore power and get pumps and valves and that kinda stuff going, but I think that’s

a reflection of the extent of damage that these plants incurred, due to the

earthquake and the tsunami and the subsequent explosions. The other thing I

thought that was interesting, and I saw this at the NEI website – the Nuclear Energy

Institute – which is http://www.NEI.org. They said on their website – and I can’t

remember the exact numbers off the top of my head, but they thought that the

tsunami that hit was about a 14 meter height, so for folks in America, 14 meters…it’s

about 39 inches, but if you use 3 feet, that’s a pretty, pretty significant wave. That’s

40-some feet. And-

Q: Is this plant right on the ocean? Or how far- I don’t think I’ve ever asked you

before.

A: Is it right on the ocean, yeah. If you look at the satellite pictures, you can see that

it’s right on the ocean. And if I remember correctly, that was about double the size

that the plant was designed for. So a lot of the buildings were well-below this wave.

So that does help explain why the diesel generators and the electrical switch gear

and that kinda stuff have been so problematic to restore. So again, I don’t remember

the numbers off the top of my head, but the NEI website had a summary of what

they thought the wave height was and what the plant was actually designed for.

Q: This is very encouraging, because it sounds like some of the nuclear

organizations are starting to try and do what we’ve been trying to do since day one,

is actually provide people with some kind of coherent story about what has been

going on and I think that’s really encouraging because at the beginning, I don’t even

think that the nuclear organizations were doing a particularly good job of – y’know,

they were releasing bits and pieces of information, but they weren’t necessarily

providing a coherent story that the average person could look at and really digest

and have a good picture of what was going on. So…

A: It’s definitely better and I think it’s a little bit easier to digest. And I think that

they definitely are trying to do a little bit better job, but it’s still pretty difficult.

There’s still no one place that anyone can go and kind of pull the whole thing

together.

Q: And that’s problematic, because back when Chernobyl happened and Three Mile

Island happened, that was- correct me if I’m wrong, but Three Mile Island was in

1979, right? And Chernobyl was ’86 and there was no internet then, and so these

days, there’s almost too many places to go for information and there’s a lot of places

where you can get misinformation and so I think it’s-

A: Y’know, I

Q: Important for people to have one place that you can go.

A: Yeah, and I don’t think it’s so much of a nuclear issue. I think when we have

time to reflect, I think it’s a good lesson learned, if there’s any type of significant

emergency situation, that the government or the organization responsible needs

to figure out the best way in which to communicate to the public. In plain English.

I think these agencies are doing a good job, but the people that work there are

engineers and scientists and they still speak in that language.

Q: And we’re an engineer and scientist, but we’re trying to speak plain English. So

you can do it.

A: Well, we are. No, we are, but also, if it was some of their field that you or I were

not familiar with, we might have a hard time interpreting it, because although I have

a lot of experience in this field from my previous jobs, there’s other fields where I

don’t have any more insight or information than anybody, so I think that’s- like I

said, I think when we have time to reflect, we’ll have to look back and say, y’know,

because of the internet, because of the information age, is there a better way to

communicate and oh, by the way, it needs to be- y’know, I said English, which isn’t

really fair, because there’s so many people around the world and a lot of different

languages. But what I meant by that was not English per se, but in laymen’s terms,

so that the average person could understand it. That’s what I meant.

Q: And I think one thing that’s been really- I mean I know that we’ve both been

surprised at how many people who have listened to these interviews and it’s been

a little bit overwhelming for us, but I think that people are there, they wanna listen

and because this disaster has the potential to affect so many people, people wanna

know and they wanna hear some of the science and the technical details. They may

not be able to understand it in technical terms, but they-

A: Absolutely, as we said-

Q: They’re interested and we’ve had thousands upon thousands of page views and

your interviews have been circulated all over the internet and so people do wanna

listen to this sort of information and this sort of story and this sort of laymen’s

explanation. And hopefully we’ve been able to provide some people with that.

A: Yeah, when I say laymen’s, I’m not asking you to dumb it down. As we’ve said a

couple times, treat us as if we’re intelligent. Give us the information, but you’ve also

gotta explain it so that we can understand it, if we’re not an expert.

Q: OK. Well, do you have anything else about the plant? Any other updates?

A: Again, I’ll echo what I’ve said for the past 2 or 3 days. There may not be great

news there, but we’re no longer in a situation where everyday, the news is getting

worse and worse and worse. So I hesitate to use the word, but right now, we’re in

a relatively stable situation. Very precarious, but each day is bringing a little bit

of progress. And the other thing that I wanna say is at times, we’ve been critical

in terms of the information that’s available, and also maybe critical of the fact that

the situation of the spent fuel pools got out of control, which may or may not been

avoidable. We’re not there, we’re not under the pressure that those folks are under,

so it’s really not fair for us to judge. And the only thing that I would add is I think

we all need to have an appreciation for the folks that are at the site, that are working

round the clock, now for 8 or 9 or 10 days straight, to try to minimize the impact of

this event and put these plants in a stable condition. And not only does Japan owe

these folks some gratitude, I think the whole world community does. It’s, I think,

similar to the situation where we’ve had in the US where you don’t necessarily have

to agree with the war in Iraq or Afghanistan, but at least have appreciation for the

troops that went there and did what was asked of them, whether you agree with it

or not, I think whether you’re for or against nuclear power, you have to have some

appreciation for the dedication and the effort that these folks are putting in on the

ground in Japan.

Q: I certainly appreciate it and I hope that the health effects that especially the

people who stayed behind during the worst of the radiation, I hope that they’re able

to treat that and (number beeps audible)- oh, are you there, Dad?

A: Sorry, I accidentally bumped the phone.

Q: OK, well, that technical problem is your fault. But no, seriously, I mean, I really

hope that, y’know, I’m sure there will be some health problems as a result, but I

really hope that they’re able to treat those people and that they don’t have long-

lasting effects, and if they do, I really appreciate what they did, because if they

hadn’t have gone in there and taken care of that situation, things could’ve been

much worse and many, many people would’ve been affected by this more than they

haven’t already, so…

A: And I think the other thing to note is some people might say, well the people that

worked there, that’s kind of their responsibility, but let us not forget the firemen,

the military helicopter pilots, I mean these people have nothing to do with this, but

nonetheless-

Q: They’re risking their lives, too.

A: Absolutely.

Q: OK, well with that, why don’t we go on to some questions. And I just want to

say something quickly… Many people have asked us to comment on new nuclear

technologies, including Thorium reactors. And what my dad and I have decided to

do is we’re actually- at the end, towards the end of these interviews – we’re gonna

give an interview where we talk about the latest technologies. We’ll talk a little

bit about it today, but one thing that we’ve really been trying to do is not comment

on things for which we – and by “we”, I mean my dad – don’t have information or

firsthand knowledge, because we don’t want to have any more misinformation

being spread, so my dad has promised to do a little bit of homework about some

of these future technologies that have been proposed and at the end, we’ll sort of

maybe reflect on this disaster and try and discuss some of these future possibilities

and some of the debate about future nuclear power at the end.

A: OK, so speaking of homework, you actually gave me a homework assignment a

couple days ago, you asked me a question about how much of the core of the Three

Mile Island Unit 2 plant was damaged.

Q: Yes. And I know you emailed-

A: And (inaudible) there. I did. So it was approximately 50% core damage and

about 90% of the fuel cladding was damaged in some way.

Q: And that’s the zirconium coating on the fuel?

A: Right.

Q: And can you just go over again, what is the purpose of that coating? Is that to

make it have some shielding so you can handle the fuel rods a little bit more easily

and control the reactions, is that what the zirconium is for?

A: Well, what actually- So the fuel is actually made into Uranium dioxide pellets.

And these pellets are approximately about a half inch in diameter and – don’t quote

me on this because it’s been a while – about ¾ of an inch high. And so you put a

whole bunch of these pellets in this tube of zirconium and then on the end, you

actually leave a gap and you put a spring in there to hold it in place. And that gap,

what happens with these fuel pellets is they actually do get a little bit of cracking

in them from the fissioning and the decay of the subsequent fission products. And

some of the fission products are gaseous, and so they’ll leak a little bit from the

pellets, but they’ll stay within the zirconium tube. And the gap that you leave with

the spring allows for that- for the expansion of that gas. Of those gaseous products.

So it’s not really like, a rod, all of one piece, it’s a bunch of pellets stacked on

top of each other. Of these cylindrical pellets. And then a spring and then an air gap,

which allows any gas that is released from the pellets themselves, will be contained

within the- what we call the fuel rod, which is really that zirconium tube, which gets

obviously welded off at each end, or sealed off at each end, and then a bunch of

pellets stacked up, and a big spring and an air gap.

Q: So why do they use Zirconium? Is there something in particular about

zirconium?

A: It’s got really good properties for use in a reactor. It sustains fairly high

temperatures, it’s got good corrosion resistance, there’s a bunch of other great

things about it that I would have to dust off 25 years-ago-studies that I did in the

Navy nuclear power program.

Q: But basically it’s just to provide some kind of structure to these pellets, which

otherwise would be loose? It’s to put them into this fuel rod.

A: Right, that’s the way that- so there is no fuel rod, per se, it’s really the zirconium

tube that these ceramic pellets are put into, which forms the fuel rod.

Q: OK, so this is actually a good thing to discuss, going into our first question. And

this came in from actually someone that I know, who said- she sent me an email and

she said that she was watching a movie – and I don’t know the movie – but at some

point in the movie, there was a nuclear power plant and they had an emergency

and to deal with the emergency, they took the fuel rods out of the reactor and they

put them onto a truck and they drove away, so that they wouldn’t be dangerous.

And she said that I ruined the movie because after listening to these interviews,

she realized that that was impossible, that you couldn’t just pick the spent fuel

rods out of the reactor and put them on a truck. So she was wondering, actually,

because she asked me, well, how do they actually move the fuel rods? How do they

take them out of the reactor and put them in the spent fuel pools, because as we’ve

discussed, why can’t they just take the fuel rods away from the site and put them

into a different tank and we discussed how the equipment to move them has been

damaged and you really have to keep them in water. But I was just wondering if

you could talk a little more about that and I guess talk about how you move spent

fuel rods and also when you move them? Does it depend on how long ago they have

been in the critical in the core, how long do they have to sit around before you move

them, that sorta thing, just about the technical aspects of moving fuel rods.

A: OK, so I haven’t looked at your website for a few days. Do you still have that

picture up that I sent?

Q: I do. And I can actually put it up again with this interview.

A: Well, so that’s as good of a picture as I think we need. So it shows where the

spent fuel pool is in relationship to the reactor. And it shows how it’s, y’know, high

up. And what actually happens is you shut down for refueling and then on top of the

reactor will kinda be this big concrete plug. And then you can take the top off the

reactor vessel. So the reactor vessel is this big, steel forging, but it has a lid that’s

held down by a bunch of bolts and you can take that off. So what you do is if you

– I think it shows it in that picture, I don’t have it in front of me – but you basically

extend the spent fuel pool. And there’s a channel that goes from the pool over to

where the reactor vessel is. And you basically fill all that up with water, as part of

the refueling process. And then you remove the concrete plug and then the top of

the reactor vessel. And so the whole reactor vessel and then channel and the spent

fuel pool become one body of water. And you use the crane that’s shown in the

picture to actually go over to the reactor, pick up a fuel assembly. So normally in

a boiling water reactor, it’s not an individual fuel rod, it’s an assembly of fuel rods,

and they’re normally 7 by 7. So 49 fuel rods are build into an assembly. And you’ll

pick up that assembly with the crane, you’ll be able to keep it under water the whole

way, move it over to the spent fuel pool and put it in its proper place.

When we refuel a reactor, we normally replace about a third of the fuel

assemblies with new ones. But, as we’ve talked about, sometimes do a maintenance

or inspections, we actually have to take all of the fuel out of the reactor and

temporarily put it in the spent fuel pool.

Q: And that’s what happened at Reactor 4, sorry, saying it at the same time.

A: Exactly.

Q: That’s why that spent fuel pool was probably- I mean, we don’t know the details,

but that’s very likely why it was more of a problem sooner than the other spent fuel

pools.

A: So actually, on the International Atomic Energy Agency website today, they

actually said on there, the dates- the last date that new spent fuel was added to

those pools. And in the case of Reactor number 4, that core was moved over there in

approximately sometime in November. Or maybe early-

Q: So that’s fairly recent, actually.

A: Early December. So that was more recent and that fuel had more decay heat in it,

which is why that one was more problematic.

Q: How often do you have to refuel a nuclear reactor, generally?

A: It depends a little bit on what we call the fuel cycle. In the early days of nuclear

power, we would do it about once a year. And then as technology improved and

we had better quality control of the fuel and we were able to do a better job of

engineering the core designs, we’ve been able to improve that to 18 months, and

in some cases, some reactors are only refueled every 2 years, now. So somewhere

between 12 and 24 months, depending on the vintage of the reactor, the core design

and the- the other factor is planning of outages. So-

Q: ‘Cause you have to shut the reactor down for that time period?

A: Right. And so the whole- all of the power sources to a grid have to be planned.

You can’t literally shut down every power plant at the same time. So part of the

determining factor is not just design, but it’s also schedule. So if you have, y’know,

pick a number. In a particular section of the grid, you have 20 different power

plants. Maybe some gas, some coal, some nuclear. The outage times of when those

are shut down have to be planned, so that you don’t have too many shut down at

the same time, because then you wouldn’t have enough power for supplying the

grid. And so normally, most of the outages take place in the early Spring and in the

Fall, because the peak power demands are during the Summer, when everybody

needs air conditioning, and in the Winter, when everybody needs heat. But even

with that said, we have to plan for not too many power plants to be shut down for

maintenance at the same time.

Q: And how long does it take to actually change out the fuel? Is that a day process,

week process, how long does it generally take?

A: To change out the fuel, normally takes a few days. It’s a- as you can imagine, it’s a

very important process and a very critical process to get exactly right, because each-

so in addition to just replacing the fuel, you often times have to move a fuel bundle

from one place in the reactor to another. Because the core design is critical. You

want to get even power distribution within the reactor. You don’t want one part of

the core to be generating more power than another part of the core. So in addition

to just replacing fuel elements, you also have to move them to different places in

the core, so that when it’s all said and done, you’re going to get a balanced power

distribution in that entire core.

Q: So is that sort of the lifespan of a fuel rod, is about a year to two years and then

you can no longer use it for fuel?

A: No, in fact, we only do- only replace about a third of the fuel assemblies, or

bundles, in an outage, so if we refuel every 18 months, then that means a fuel

assembly’s in there for 3 cycles, or 4 and a half years.

Q: OK, and at that point, and I know another- we haven’t really talked about this, but

unless you do some recycling of the fuel rod, at that point, the fuel rod is considered

spent and it can no longer be put back into the reactor?

A: That would be correct.

Q: OK. So then you move the fuel rods to the spent fuel pool. And then they have

to sit there for a time period and then- I mean, this is one of the big problems of

nuclear power, and then they have to do something else with those fuel rods. And

so-

A: So normally what happens is they’ll be in the spent fuel pool for a number of

years, to completely cool down. And then in the US, the original plan was that the

United States Government was going to take possession of the fuel assemblies and

they were going to store them all in Yucca Mountain.

Q: Which has now been shut down.

A: And after many, many dollars were spent and studies and research and

construction, ultimately, we decided not to do that. So we’ve run out of space in the

spent fuel pools at a lot of the reactors. So what’s happened is – I mentioned this in

one of the interviews – we do what’s called “dry cast storage”. And at Fukushima,

they actually have some dry cast storage, as well. Even though Japan is a country

where they do some fuel reprocessing, or recycling. And what it is is it’s a big

concrete container and you can take the very old fuel rods that don’t really need

any significant cooling anymore. And you can take them out of the pool and you

can put them in these big concrete paths and they’re kept physically separated so

there’s a little bit of air flow around them, and they’ve cooled off enough that just

the natural air that would be out there would be enough to provide the remaining

cooling that they would need. And they basically sit in these casts until there’s a

solution for either disposing of them or hopefully recycling. Because one of the

things we haven’t talked about is, in a reactor – and it’s not a good word, because

fuel doesn’t actually burn, but because of the, I think, the history of power plants,

we talk about burn. You can only burn the amount of fuel above what’s required to

have a critical mass(?). And so when the- without going into a lot of detail, when

a fuel rod is spent and can be no longer used in a reactor, there’s still a lot of good

stuff in there. There’s still Uranium, there’s Plutonium, that we talked about that can

also be used as a fuel, and the amount of nuclear waste there would be significantly

reduced if we could recycle that- the good stuff, and reuse it in another fuel rod and

that- We talked about Reactor 3, which does use mix oxide fuel. And that mix oxide

fuel is fuel that’s partially recycled and made into a new fuel rod.

Q: And just to repeat, we currently do not do this in the United States, we currently

do not recycle fuel rods?

A: We do not recycle fuel rods in the US for commercial nuclear power plants, but

many countries around the world – France, Japan – do recycle their fuel.

Q: And the problem with that is if you do do recycling, you can significantly reduce

the amount of nuclear waste that you ultimately have to store in spent fuel pools

and in dry cast storage. Plus, the other thing we haven’t really talked about is, and

I don’t think we wanna get into this tonight, is you also don’t have to then go in and

mine more Uranium and more fuel for these power plants, you can actually recycle

some of what you’ve already used.

A: Correct, no it’s – it would definitely be a step forward, I think, if we were to

reprocess fuel. We’d reduce the amount of waste that we have and be able to

reuse the good stuff as new fuel. It’s kinda the same thing, if people recycle their

aluminum cans, their plastic bottles, y’know, you can make it into usable things and

reduce the amount of waste, so…

Q: So do you have any insight – I know this is probably a politically-charged

question – but why don’t we recycle in the United States?

A: The concern in the US was because these spent fuel rods have Plutonium in

them, that somehow they were going to fall into the wrong hands and somebody

was going to make a nuclear bomb out of it. But the reality of it is that it takes

such sophisticated technology, and it’d have to be handled with such care, because

they are very radioactive, that it’s pretty implausible for anybody besides the

government or a utility consorting sponsored by the government that would have

the wherewithal and the technology and the equipment to do this kind of work.

This is rocket science, y’know…

Q: Nuclear version.

A: It really is, I mean – and I think that’s part of the reason why it’s been helpful to

have these conversations is, let’s face it, and this is rocket science that we’re talking

about, it’s not something that’s intuitive and I hope that we’ve been able with these

talks to better explain this stuff to you, but it’s pretty far-fetched scenario to think

that some terrorist group would be able to get their hands on a fuel rod and have all

the technology and the equipment to reprocess that and get the Plutonium out of it

and make a bomb out of it. I mean, that’s-

Q: And clearly other countries, such as Japan and France, are not concerned about

this and they’ve not had any problems, so…

A: Well, concern is not the right word. I mean, a lot of precautions have to be taken.

If the technology upon which the spent fuel is transported, y’know, police escorts, I

mean there is a lot of precaution taken. But again, even if somebody should get their

hands on one of these, to have built a multi-million dollar plant to reprocess these,

without anybody knowing about it, it’s a bit of a stretch.

Q: OK. And just to finish this story, so at some point, you either, y’know, you’re

not allowed to recycle or you can’t recycle anymore. At some point, you do have

to consider long-term storage of the fuel rods and you’ve talked about this before,

there’s actually 2 types of nuclear waste, there’s the fuel rods and then there’s

everything else that has been made radioactive, like gloves and suits and things.

And those are the two types of waste that you have to worry about, sorta what to do

with long-term. So I guess let’s just stick with the fuel rods to start with. So I know

that they were thinking about putting them in Yucca Mountain, and I won’t talk

about this today – I actually visited Yucca Mountain several years ago on a geology

field trip and something that was interesting – and I won’t talk about the details – is

that that’s actually a region that is…there are many faults, there’s been volcanism,

it’s not actually the most geologically-stable region, it’s wouldn’t be a place that I

would personally recommend, as a geologist, that you would want to store your fuel

long-term. But for whatever reason, maybe because of the geology, they’ve decided

not to go through with that. But you do need some place where you can store these

for a long time and I guess the question is how long do you have to store these

before you can insure that they’re not going to be causing any problems for people?

A: A very long time.

Q: Where do you store them?

A: A very long time.

Q: Can you define “very long”? Thousands of years? Millions of years?

A: Thousands of years.

Q: OK. And it’s really difficult, I mean, I know one thing, y’know, at Yucca Mountain,

they have to predict what the geology is going to be doing a thousand years

in advance and that’s something that’s very challenging to do, I mean we have

trouble predicting climate, we have trouble predicting what a volcano’s gonna do

a thousand years from now and you can do the best you can, but it’s not- y’know, if

you look at how difficult it is to predict the weather, sometimes, forecasting in the

future and it can be challenging and there’s many variables and so finding a safe

place to store these is, y’know, there are places to do it, but it’s challenging.

A: As somebody that worked in that field, there’s no doubt that this is a major issue

that there is no perfect solution for. And I think especially for people from the US.

We’re- we represent what percent of the world population?

Q: I don’t know, but it’s not very much.

A: 5 percent or less?

Q: I’m gonna Google it. Continue.

A: It’s a few percent. And we use something on the order of 25% of the world’s

energy. And so first and foremost, I think that it’s incumbent upon the United

States and other Western societies to find a way to use less energy on a per capita

basis than we currently do. Because no matter what choice you pick, whether

it be natural gas fire plant, coal plant, nuclear plants, there’s something that’s

fundamentally unacceptable about all those things, in terms of the impact that is has

on the Earth. And so first and foremost, I think we need to challenge ourselves to do

a better job of finding ways to reduce our energy usage. And then you-

Q: And also-

A: Then you can get into a debate of what’s the best choice and definitely

everybody- a lot of countries now have set goals for renewables. And renewables

are good, obviously. You have solar, you have wind, they have downsides, too, in

terms of sometimes they’re not available. If the wind’s not blowing, or if the sun’s

not shining, then you can’t always count on those, so somewhere along the line,

with today’s technology, you are going to have to use some coal, some gas and

probably also some nuclear, but – And then you have to balance the pros and cons

of all of those. And I think the challenge for us is can we do that objectively and

scientifically? Because a lot of times, the decisions are made emotionally. And

again, there- the best kilowatt is the one we don’t use. We’ve got- Western Society

has to find a way to be more energy efficient.

Q: I’ll just add a couple things to that. First thing I wanna say, too, is I travel in

my geology research and for personal travel quite a bit in the 3rd world and the

standard of living there is obviously- my fiancé is actually from South Africa and

traveling in South Africa, you see the way that people live and it’s terrible and you

want to improve the living conditions of these people. And if you think about that, if

you think about world population increasing. And also I really hope that we are able

to improve living conditions in many of these 3rd world countries. There are many

developing countries, if you look at China and India. So if there are- our energy

needs are really going to increase and if everybody uses energy the same way that

we do here in the United States, there’s just no way that we’re going to be able to

supply it and these issues – debates about nuclear power and other power – they’re

just going to become more intense, because if everyone has the standard of living

and the same energy use that we do- the average person in the US does, there’s

just no way that we can sustain that, so we really do have to think about these

things. And I also want to say – the second thing – is I really agree with what you’re

saying, that, y’know, when you have this many people living on a planet, you’re

gonna have to choose something and it’s not gonna be perfect. But if we make that

choice, it shouldn’t be emotional, it should be scientific and we’ve really tried in

these interviews to stick to the facts and stick to the science. And I think that, again,

whatever your opinions are about nuclear power, please don’t make those opinions

based on emotion, make those opinions based on on the science and on the facts and

really try to educate yourself – not just about nuclear power, but about all energy

options. So…

A: There- y’know, I mean… There’s no such- in my opinion, there’s no such thing

as a good power plant of any type. And the best thing that we can do as a society,

or as a global society is to continue to use our brains and our engineering and our

science to come up with ways that we can be more efficient with our energy use.

And we are making great strides there. But as you pointed out, as the population

expands, even if we reduce the per capita consumption, the overall consumption

may go up. And I think we have to re-double our efforts to be more energy efficient,

so that we don’t need as many power plants of any kind. And we definitely need

to continue to use our technology in the renewable areas. We need to get solar to

the point where it’s really, truly economically viable without subsidies. And there’s

great strides being made, from shingles that you can put on your house that are

solar panels as well. Without actually having to have a fragile solar panel up there,

that’s a technology that can be made right into the roof of your house and so I’m

confident that with all the smart people we have in the world and all of the science

and engineering talent that we have, that as a global society, we will engineer our

way out of this, but we got quite a bit of work to do.

Q: I agree and I also don’t think that you should pick your favorite power plant and

vet(?) that power plant against everything else, I mean I think that we need to work

our many fronts and I don’t think that any one energy source – and I would love to

be proved wrong on this – I don’t think there’s ever going to be one energy source

that’s perfect or that can meet all of our energy needs, and so I think you need to

continue forth scientific research in as many fields of energy as you can and some of

those might end up being dead-ends, but I think only if we do that, are we going to

really make sure that we are going to meet our energy needs in the future and to do

that in the future in the safest way possible and the way that impacts our planet the

least. So…All right…

A: The other consideration we have – and we can get off of our soapbox – is that

different countries around the world have different natural resources. So some

countries, if they choose that they want to have a lot of nuclear power plants, that

may also be the countries that don’t have other choices. And I think that’s important

for all of us to keep in mind, that not everybody has gas or oil or coal as options.

Not everybody has a climate that’s conducive to a lot of wind power or solar. So

different decisions are going to be made in different parts of the globe and again, I

just hope, as a global community, as time moves forward and we can improve our

science and engineering and our energy efficiency, that we can do a better job going

forward and we just won’t need as many power plants of any kind.

Q: OK, well, since we’ve been on our soapbox for a while, I think one of the

questions that I was going to ask you, I’m actually going to ask in a later interview.

Somebody wanted to know if you thought this was a setback for nuclear power and

if you could comment on some future technologies and I think we’ve sorta promised

to do that, kind of devote a whole interview to that – talking about how nuclear

power technology power has improved. Again, the Fukushima plants were built in

the 60’s and 70’s and there has been a lot of progress made, so I think we’ll save that

for another interview.

A: Yeah, let’s save that- let’s answer that question when we kinda do our wrap-up,

whenever that comes.

Q: Yeah, and again, that’s been a very common question and we’ve kinda

purposefully avoided that question because at first, when there was a crisis,

it wasn’t really relevant to the situation at hand, because as great as the new

technology is, it wasn’t at Fukushima, so we tried to really focus on the situation at

hand, but we will address that, we will try to research that.

A: Alright, well, let’s answer a couple questions and then we’re gonna need to wrap

up.

Q: Yeah, so this is the last one. And I think it’s actually relevant. So somebody

wrote in and they were concerned because the Vermont Yankee Power plant, which

you actually used to work for Vermont Yankee, so maybe you can comment on

this. It has been around for 40 years and either just received or is requesting to

extend its license for 20 more years, so that it can run for 60 years and, from what I

understand, and what this listener understands, Vermont Yankee is actually pretty

similar to Fukushima- the Fukushima 1. And this person wanted to know if, in light

of the recent events in Fukushima, if you think it’s a good idea that they’re extending

that license or not?

A: OK. So I don’t work in the industry anymore, so I don’t keep up with everything

that’s going on. But with respect to Vermont Yankee, originally, when the titles

were licensed, they were licensed for 40 years. And that 40 years started from the

day that you start doing construction on the plant. Or the day that the NRC granted

that license. What plants were able to do was make a construction recapture, so

that the 40 years started from the first time that you started operating. So that

would involve-

Q: How long does it take to build a power plant?

A: It wasn’t uncommon to take 4 or 5 years to build a power plant. Some of the

later ones stretch longer than that, because of all of the design changes that were

required after the Three Mile Incident, but typically again today, it takes about 4 to 5

years to build a nuclear power plant, in the time you turn that first shovel of dirt

until you’re able to operate. So in any event, that was done and the 40 years for the

original license was from the date that they first started operating. A lot of plants in

the US have been licensed for an additional 20 years and I think we talked about it

in one of the interviews. Even though the plant is 40 years old, most of it isn’t 40

years old. Many, many pieces and parts are replaced, turbine rotors… Vermont

Yankee went through a power upgrade a few years ago, so a lot of parts in the plant

were replaced, new electrical generator, so there are parts that are 40 years old, but

it’s not like your car. You can imagine that if you had- if your car is a nuclear power

plant, the frame might be 40 years old, but everything else – the engine, the interior,

all the body panels, they’ve all been replaced and they’re not 40 years old. But

nonetheless, the process is to basically demonstrate that you’ve come up with the

plant, you’ve made all the safety improvements and you apply for this 20 year

license extension. And it’s really complicated for the older plants, because they have

changed over the years. If you can imagine, these plants that were designed in the

60’s, we didn’t have computer-aided drawings and the computer technology that we

have today to do the calculations… I mean, these plants were designed with slide

rules, not computers. So the plants have spent a lot of money over the years to go

back and recalculate everything and revalidate all the assumptions that were made

in the engineering, from when the plant was originally built. In Vermont Yankee’s

case, the NRC did just grant their 20 year life extension, but in the state of Vermont,

they also need a certificate of public good from the Public Service Commission, and

last year, the Vermont State Senate voted to not authorize that. So Vermont Yankee,

as far as the NRC is concerned, can operate another 20 years, but unless the state of

Vermont Senate takes another vote, and authorizes the Public Service Order

Commission- I can’t remember what it’s called. To issue the certificate of public

good, they won’t have the green light to operate from the state of Vermont.

Now getting to the question that the person asked…. What do we think about

the fact? And I go back to what we said in one of the first couple of interviews that

we did. And I said, in light of what’s happened in Japan, where we had an

earthquake that’s beyond the design basis and we had a tsunami that was beyond

the design basis, we need to go back and look at all these plants and look at the

design basis and see if, given what we know today, we’re still OK on the design basis

of the plant. So Vermont is obviously more geologically stable than Japan, but we do

have earthquakes in New England. So are our assumptions still correct, about

what’s the worst-case earthquake? What’s the worst-case winds that we might have

from a hurricane? Or –

Q: A Nor’easter, for instance, could hit Vermont Yankee, theoretically.

A: A Nor’easter, or y’know, we don’t get tornadoes very much New England, but we

still get them occasionally.

Q: On speaking to the geology point, just for a minute, Vermont Yankee, geologically,

it’s very stable. There is a passive plate boundary, so if you want to know more

about why there was an earthquake in Japan, I’ll post a link, I’ve blogged about it

earlier, but basically, Japan, there are three tectonic plates that are interacting. And

that creates an area where there are going to be volcanoes and earthquakes and

on the East Coast of the United States, we don’t have plate boundaries, it’s actually

one plate that continues out all the way to the Mid-Atlantic ridge, it’s what’s called

a passive plate boundary, and so there’s really no friction or tension, so there isn’t

really a geological mechanism to get an earth quake of the magnitude that we

had in Japan and a tsunami that we had in Japan. However, on our other coast, in

California, we have the San Andreas Fault, which is a very large fault, and we also

have tectonic plates further north in Oregon and we have our volcanoes. And so

we, from a geologic perspective, I would actually be more concerned about nuclear

power plants that are out in California. And actually, thinking about the design basis

for those and really, I think that all power plants should consider this, I think that

what Japan is showing us is that maybe the design basis really isn’t the worst-case

scenario.

A: And so that I think is the key question to be asked is, in light of what we’ve

learned over the past couple weeks, are our assumption about the design basis

of the plant still valid? And Vermont Yankee’s on the Connecticut River. Are our

assumptions about the worst-case floods still valid? Or do we need to take a look at

earthquakes, natural disasters, those type of things, and make sure our assumptions

are still valid. And if they’re not, then that has to be looked at from an engineering

perspective and say, OK, then what are the new assumptions? And do we still meet

the criteria of whatever the new assumptions are? And if after all of that review,

the answer is yes, then by law and by practicality, the plant should continue to run

for the duration of their license. But I think one of the important things to do is to

apply the lessons learned and I know the president and the chairman of the NRC

has said they are going to go back now and take a look at all the plants in the US

and hopefully look at the design basis and make sure that, from an engineering

perspective, that any information we have is applied and that we still can- that

our assumptions are valid and that the risk – because there’s always a risk – is

acceptable.

Q: I think that some more geologists should be talking to some nuclear engineers

and some people who are experts at risk analysis. I guess not every geologist has a

father who’s a nuclear engineer, but it sounds like some dialogue between people

who have some knowledge about what these natural hazards might be and people

who know about nuclear power plants and people who are used to assessing risks

should all get together and really think about this issue seriously. And I’m glad to

hear that the president is pushing for that.

A: It’s not just geologists. So for every plant around the world, we’ve made

assumptions on what’s the worst-case scenario for when.

Q: Meteorologists, maybe lots of scientists.

A: And we need to look at what happened in Japan and say, well, if that was a- and

I don’t know, but if that was a 1 in 10 thousand year-event, how did it happen?

Were our assumptions invalid? Because it may turn out that there could be a

plant somewhere in the world where the worst-case wind that it was designed

for turns out to be too low because our assumptions were invalid. And that’s my

point. We’ve gotta go back and look at the design basis of each plant. We owe it to

ourselves, we owe it to the general population and make sure that our assumptions

are valid. And my guess is, in probably 99 percent of the cases, we’re gonna go

back and look at it and find that we’re fine. Especially for some of the older plants,

because they were designed with slide rules, a lot of times, they were over-designed,

because we didn’t have the computer technology to exactly calculate something. We

didn’t have computer drawings, so in a lot of cases, these plants were over-designed

and there’s a lot more design margin in them, versus maybe something that was

built more recently, that we’re able to calculate more precisely.

A good example of that would be, you take an airplane leg of a DC-9, a few of

which are still flying with Delta. Because of the time frame that those planes were

designed and built, those planes are just over-built, I mean you could probably

almost fly them forever, because they ‘re just really solid. And today, obviously,

when we build a plane, we got all the computer technology and we calculate how

many times you can take off and land before we break a landing gear. And it’s the

same type of thing, when we didn’t have the sophisticated technology to calculate

things as accurately as we’re able to do now, we built a lot more design margin into

it. So my guess is in a lot of cases – even if the design basis for some of these plants

change, we’re probably going to be OK because they were over constructed. But

there may be some cases, where we find out it could be higher than we thought. Or

that tsunami or wave from the ocean or that wind could be a little stronger than we

thought. And we might have to go back and make some modifications on some of

them.

Q: And also, not only has there been some advances in the nuclear power industry

and technology, but I would say that in geology and in other natural sciences, there

have been improvements in our estimates, we- compared to 40 years ago, we also

have computers and we have better models and so if the plants were designed-

and I don’t know if they’ve updated this, but if the plants were designed for what

we thought was the worst quake- earthquake or Nor’easter or winds or whatever

40 years ago, I imagine that because there are many scientists working on those

problems too, you’ve actually updated those estimates and there’s probably new

risk assessments available for those. I don’t know, they’ve probably gone back and

reassessed that to a point, but it’d be worth evaluating that on a large scale and I

think Fukushima will hopefully inspire the United States and other countries to take

a close look at that.

A: Yeah, I mean no doubt that over the years, these things have been looked at over

and over again. But now’s the time- definite time to take a step back and say, woah!

We just saw something here that nobody expected to happen. Does that apply

anywhere else?

Q: Or is that truly a one in a- I actually don’t know- one in 10 thousand case or

something. I should actually talk to some geologist friends about how common this

is, but… we should probably figure out what the probability of that event was. Was

this just a very unlucky improbable event, or was this something that is geologically

plausible, could happen again or could happen in a different way somewhere else? I

think it’s good to think about all these things again.

A: All right.

Q: All right, I think it’s time for both of us to get to bed, so… All right, have a safe

trip home, Dad, and I’ll talk to you- are we going to talk to you tomorrow?

A: I don’t think I’ll be able to because of my travel schedule, so maybe Thursday.

Q: OK, our next interview will be on Thursday. And please do continue to send

questions. Fortunately our readership has leveled off, probably because the interest

in the news is less, and so we’re receiving fewer questions, which is good because I

was pretty overwhelmed with them for a while. So if you didn’t get your question

answered before and you really want to know the answer, send it in again or send in

new questions and we’ll continue to answer questions for a while. So…all right.

A: OK.

Q: Good night, Dad.

A: Good night.

A Quick Note: Next Interview Scheduled for Evening of 3/22

My father and I were originally going to do another interview this evening. However, we’re both exhausted. Earlier today my dad had to make his way through a March snowstorm to fly out for a business trip, and he’s very tired. I’m also very tired– over the past few days, I have been doing hours upon hours of chemistry in lab in addition to the time I’ve been putting into these interviews. Thus, we are going to skip tonight’s interview so that we can both rest.

Tomorrow and Wednesday I am going to be measuring uranium and thorium isotopes (in uranium and thorium concentrates which I’ve extracted from rocks from Oman) on the NEPTUNE mass spectrometer here at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Since machine time on the NEPTUNE costs about $1300 per day, I will not be able to record tomorrow’s interview until the evening sometime. I need to make the best use of my time on the NEPTUNE. I’ll try to have Interview 10 posted by late evening tomorrow night (EDT). If you have any questions you want me to ask my dad tomorrow evening, please email them to georneysblog@gmail.com. Thanks!

9th Interview with My Dad, a Nuclear Engineer, about the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant Disaster in Japan

Update: Gerald has kindly hosted all of the new audio files. I will update all the audio links (some of which are broken) soon– tonight or tomorrow. DONE Meanwhile, you can listen to all the audio files on the new vimeo channel Brandon and I created. You can also listen to most of the interviews on Brad Go’s YouTube channel.

Here’s the vimeo channel:

In the interview today, we talked some about radioactivity and uranium isotopes. I actually study uranium-series isotope chemistry in rocks. A part of my PhD thesis research is using the decay of uranium-series isotopes found naturally in all rocks (at low, non-dangerous levels, in most cases) to determine ages of rocks and minerals. I am actually working on this chemistry today in lab. When I eventually return to blogging about geology, I promise to write more about my uranium-series research in geology. For now, I though it would be good to talk briefly about uranium and its isotopes since this is relevant to nuclear power. My dad and I also discuss this topic in our interview. You can see my isotope discussion and some useful figures after the jump.

Because of work obligations, our next interview will not be posted until late tomorrow evening (EDT).

There is text on uranium and its isotopes after the jump. Please transcribe this interview if you have time and interest– just post a comment below so that others do not duplicate your effort.

Update: Thanks to Michelle, a transcript is now available after the jump.

|

| Cartoon of an atom. Note that this cartoon is not to scale and the nucleus is very, very small. Cartoon taken from here. |

|

Radioactive Decay of Uranium-238 and Uranium-235:

Uranium-238 and uranium-235 are both radioactive. A radioactive atom is an atom that does not have a stable nucleus. Because its nucleus is not stable, a radioactive atom will eventually decay to a different atom that is stable. This decay occurs at a steady rate that depends on nuclear properties but which can be measured (and used to date rocks!). Some radioactive atoms just go through one decay because the first decay brings them to a stable nucleus. However, sometimes radioactive atoms have to decay through a whole series of other radioactive atoms until they finally reach an atom that is stable. This is the case with uranium-238 and uranium-235. Uranium-238 decays through a whole bunch of intermediate, also radioactive atoms until it reaches stable lead-206. Similarly, uranium-235 decays through a whole different bunch of intermediate, also radioactive atoms until it reaches stable lead-207. |

|

| Figure taken from Principles and Applications of Geochemistry by, Gunter Faure, 1998: pg.280. Click on the figure to view larger. |

***********************

Transcript for Interview 9:

Q: Good afternoon, Dad.

A: Good afternoon.

Q: All right, we’re gonna continue with out interview series. My name is Evelyn

Mervine and this is the 9th in a series of interviews with my dad, Mark Mervine, who

is a nuclear engineer. If you would like to listen to any of the previous interviews,

you can find them on my geology blog, Georneys, which is G-E-O-R-N-E-Y-S.

Georneys.blogspot.com. And in today’s interview- sorry, before we get started, I’ve

been try to give the time and date so…. Today is the 20th of March and it’s currently

4PM Eastern Daylight Time.

And as I was saying, in today’s interview, there’s gonna be 3 parts – the first

part, my dad is going to give his usual update about what’s going on at Fukushima.

In the next part, in the previous interviews, my dad has promised that he would do a

little homework and talk a little bit more about radioactivity and radiation, so he

will do that. And then finally we’re gonna ask as many questions- I’m gonna ask as

many questions as I can and my dad will answer those. And then again, because we

are receiving so many emails, we can’t answer every single question. With that said,

Dad, would you like to start with your update?

A: OK. So just as a reminder, we’re talking about the Fukushima 1 nuclear power

plant in Japan. And this power plant actually consists of 6 boiling water reactors.

And the ones that we have been most concerned about is Units 1 through 4. Let me

just quickly give an update on Units 5 and 6. So as we indicated a couple days ago,

they have been able to get a diesel generator started at Unit 6 and run a cable, which

essentially is the equivalent of a long extension cord over to Unit 5, to be able to

begin to restore power to both of those units. They now have 2 diesel generators

up at Unit 6 and they are supplying power to Unit 5. And in both of those reactors,

they’ve been able to establish normal heat removal capabilities. And they’ve also-

the reports conflict a little bit – but either removed some panels from the reactor

building or drove some holes in the reactor building, but if there was a buildup of

hydrogen, they would allow it to escape before it became at a level that it would

be explosive. Given that they were able to restore power and cooling, and hoping

they don’t have any more issues with those diesel generators, that’s probably not a

concern and we should consider that those two units are stable. Another reminder,

those two units were shut down for maintenance at the time of the earthquake.

Units 1 through 3 were operating at the time of the earthquake, and Unit 4

was shut down. And all the fuel in Unit 4 had been moved to the spent fuel pool –

the entire core had been taken out, not just 1/3 of it, which is normally done for a

refueling outage. And the (?) there would be that they were doing some more

extensive repairs or inspections of the reactor vessel and they needed to remove all

of the fuel, but in any case, all of that fuel was moved to the spent fuel pool for Unit

4.

Over the past few days, I think most people are aware of, they’ve been

pumping seawater into reactors 1, 2 and 3 and maintaining a relatively low pressure

in those reactors, while venting steam. The reactor buildings of Units 1 and 3 were

severely damaged by hydrogen explosions, early- relatively early into this event.

There’s also been an explosion in Unit 2, but it was less significant and there is less

damage in the Unit 2 reactor building. And they have removed a couple of panels

from the Reactor 2 building, such that if there were more hydrogen to build up, it

would vent out and not become combustible or explosive. In Unit 4, even though

the reactor was not operating and all the fuel had been removed, there was a

buildup of hydrogen in the reactor building, which did cause an explosion and the

Unit 4 reactor building has been seriously damaged.

What’s been going on in the last 24 to 36 hours is it’s continued to inject

seawater into reactors 1, 2 and 3, and maintain pressure by venting. They put a

tremendous amount of water into the reactor 3 building by using fire equipment

and water cannons and in the past 24 hours, they’ve done the same with Unit 4. And

the purpose of doing that was to try to get water into the spent fuel pools at those

two buildings. They are also in the process of trying to run power from the grid to

those units and although I haven’t heard a lot about the progress today, the last

update from yesterday was that they had managed to bring that cable over to Units

1 and 2. And they’re in the process of- first, they’re gonna restore power to the

control room and then try to work their way through and see if they can get power

back to at least 1 cooling system. And they’re starting with Unit 2, because the

damage from the earthquake and from the explosions is less significant in Unit 2

and I think that’s a good strategy – when you’re trying to manage a situation like

this, where you have multiple things going on…they’ve got Units 5 and 6 stable, so

for the most part, from an operational perspective, that’s not something they have to

worry about in real-time. If they can restore power into Unit 2, which is the least

damaged, and get that one in a better condition, then they can focus on the

remaining problems at 1, 3 and 4.

So that’s the current status. Now we got a lot of questions and I have- I said

last time, and I copied you, Evelyn, that I would try to answer some questions about

radiation and radioactivity. I actually ended up talking a little bit about it in my

interview with Anthony. But I’ll just do a little bit of a recap. First off, I would

encourage people to take a look at Wikipedia. There’s actually been some great

information added in the past 24 hours, so if you take a look at Wikipedia for the

Fukushima 1 Nuclear accident, there’s a lot of good information there. And also, if

you do a search for “nuclear fission product”. There’s a good article there. And

they’re a little bit technical, and maybe a little bit hard to understand, but in

conjunction with what I’m about to explain, hopefully that will form a complete

picture for folks.

So we talked about this over the past week or so, but when fuel’s initially put

into the reactor, it’s Uranium. And it’s slightly enriched, so it’s approximately 96,

97% Uranium-238 and 3 or 4% Uranium-235. Now, Uranium is radioactive and-

naturally radioactive- and it decays by giving off alpha particles. But as I’ve talked

about, alpha particles don’t have a good penetrating range, and they can actually be

stopped by just a sheet of paper. So normally, alpha particles are not much of a

concern if you get them on you, because you’re outer layer of skin will stop them,

certainly your clothing will. But the big concern with alpha particles is if you ingest

them, or if they get in your eyes, so if you breathe them in or they’re on your hands

and you get them in your food, or if you get them in your eye, where your eye

doesn’t have the same protection your skin does, there’s concern about that. But

normally, a fuel rod, when it’s new, because the fuel is encased in zirconium, the

alpha particles won’t even penetrate that and you can really- other than you wanna

be wearing gloves, because you don’t want to damage the fuel or scratch it – you can

actually handle that without any concern. Once it’s in the reactor, though, it’s a

different story. So Uranium-235 will absorb a neutron and fission and break apart.

And when it does, it forms another- a number of, what we call, fission products. And

that’s where that article on Wikipedia comes in really handy if you wanna get into a

little bit of detail of what the different fission products are. But the most significant

ones that we talk about from a human health perspective are Iodine, Caesium,

Strontium. In particular, the reason that those three are significant is iodine can be

absorbed by your thyroid and your thyroid is one of your more active glands. So if

you get a lot of radioactive iodine in there is bad because radiation, or radioactivity

on your glands would have a tendency to cause more cell damage than, say you got

something on your skin, where the outer couple layers of your skin are normally

dead, so on your skin, it’s not gonna have that much of an impact. The two others,

Strontium and Caesium also replace what’s naturally in your body. So Strontium

will be absorbed by your body, similar to calcium. And so it gets into your bones

and bone marrow. And then Caesium is a lot like potassium to your body, and we all

know that we have a lot of potassium in our bodies, so the Caesium will be absorbed

instead of the potassium. So we talk about those a lot. And that’s why it’s a concern

when these things get into the environment. So I thought about the (?) particulates

that would be found in Uranium. The other thing that happens in nuclear fuel,

which we talked about is, the Uranium-238 does not fission, but it will also absorb a

neutron. It just doesn’t spit apart, it becomes Plutonium-230- I’m sorry, it becomes

Uranium-239. And after a couple decays, it becomes Plutonium-239. And

Plutonium has a very long half-life and will stay in the environment for a long period

of time and again, you have the decay that was- of Plutonium that would be very

dangerous to human health if it was ingested.

Q: And Dad, just to interject, that’s because it decays more quickly than the

Uranium? Is that why it’s more hazardous?

A: Well, it actually- for a given quantity, it has a very long half-life, which means it

actually decays less quickly.

Q: OK, I wasn’t sure what the decay rate was.

A: But if it becomes airborne or gets onto, y’know, food that you might ingest and it

gets into your body, then that’s problematic. So just like it would be problematic to