|

||

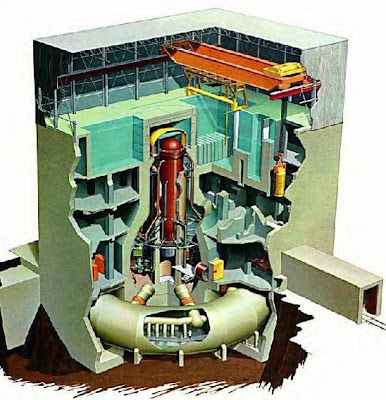

| Picture of a Boiling Water Reactor Nuclear Power Plant like the Fukushima Plants. My dad refers to this image in his interview. |

Update: All the interviews are now available on a vimeo channel. Here’s the vimeo channel:

Update: Announcing Daily Updates from My Dad

My dad refers to this article in today’s interview:

Here is a vimeo video of the interview:

Update: I have cleaned-up the original transcript.

EM = Evelyn Mervine

MM = Mark Mervine

MM: Hello.

EM: Hello. Are you ready for Part III of our nuclear power interview?

MM: I am.

EM: Okay. Before I begin this interview, I just want to quickly say that this is the third in a series of interviews with my dad, who is a nuclear engineer. I encourage you, if you haven’t done so already, to listen to Interviews 1 and 2, which can be found at my geology blog Georneys (georneys.blogspot.com) or they can be found on the Skepchick blog (skepchick.org). I’m not going to introduce my father again. If you want to see his qualifications, please look at the first interview— listen to it or read the transcript— but I’m actually just going to start off, and I guess I’ll start with asking you to maybe give us an update on what’s going on at the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant in Japan. There has been a second explosion, as I understand.

MM: So, let me give some good news first. The plant that we’ve all been focused on is the Fukushima 1 plant. There’s also a Fukushima 2 plant which is a few miles away which has 4 nuclear reactors. And the good news there is they’ve been able to completely cool down one of the reactors, and they’ve been able to restore normal cool-down to two others. So, the situation at that site has dramatically improved over the last 24 hours.

EM: Excellent. That’s very good news.

MM: Now, with respect to the Fukushima 1 site, the situation has gotten dramatically worse in the last 24 hours. So, as was seen in the news— and I’m sure people have seen the video or the photos— they had a similar explosion in Reactor 3 as to what they had in Reactor 1, due to the pressure that they were relieving from the containment, primary containment, into the secondary containment. As we explained yesterday, when the fuel cladding reaches 2200 degrees Fahrenheit, it will interact with water to form zirconium dioxide and H2O [water].

And the venting of the steam in order to reduce pressure in the reactor and in the containment obviously included enough hydrogen to set off an explosion which has destroyed the top of the Unit 3 reactor building.

EM: And the other thing that I read in the news— I don’t know if you can confirm this— is that that explosion actually damaged some of the cooling systems for another one of the reactors at Fukushima 1.

EM: Oh, it’s actually above the water level. And can you explain why that is bad?

MM: That’s bad because if you don’t have water to cool the fuel, it will heat up and start to melt.

EM: Now, from what I understand, they were actually using sort of one of their normal cooling systems for that Number 2 reactor?

MM: That’s correct, and they’ve now shifted to pumping seawater and boron into that reactor, but at the moment, according to the latest report I’ve seen, they are unable to do that because of the pressure buildup in the reactor and the valve that they need to open to relieve the pressure which would allow them to pump more water in there has failed.

EM: Yes. That doesn’t sound very good.

MM: They’re in a situation where the pressure needs to be relieved, and to explain a little bit, the pump that they would be using to pump the seawater in is a low pressure pump. So the pressure in the reactor has to be below the output pressure that that pump can produce in order for the water to flow.

EM: So, I have two questions for you related to that. The first one is, if they are unable to get seawater in there—I know that, fortunately, in the explosions that have happened, the containment has, has stayed intact for the other two plants, which is very good because it means that there shouldn’t be a large radiation leak. In this case, with Reactor Number 2, is there any danger that if there is an explosion this might be different? That this actually might affect the containment? Or should that containment remain intact?

MM: They need to reduce the pressure in the reactor and in the containment in order to prevent damaging that primary containment structure.

EM: So, there is a risk— a potential risk— that that primary containment could be damaged?

MM: Correct.

EM: In your opinion?

MM: Normally there is a pump that would spray water into the containment that would reduce the temperature and pressure. But those have not been available since about an hour after the earthquake. So, they need to be able to open these valves and release the pressure as they did in Units 1 and 3, and I’m sure they are furiously working on that as, as we speak.

EM: And so if that primary containment is breached, then the situation could become much more serious, in your opinion?

MM: It could, but at this point in the game, let us hope that they are successful in reducing the pressure and that we don’t have to go down that path as to what could happen.

EM: Okay. A follow-up question that I have for you, related to the same thing, is we’ve been seeing in the news that they’ve been pumping boron and seawater into Reactors 1 and 2, and clearly that didn’t work perfectly because there were explosions in these auxiliary buildings. The containment did stay intact, so that was good, but there were these explosions so clearly that strategy isn’t working perfectly. Can you comment on maybe why that we are having these explosions, why we had the explosion at Number 2 even though they were trying to provide the seawater and boron?

MM: Okay. So to clarify, the explosions have occurred at Units 1 and 3.

EM: Sorry. That was my error.

MM: Not Unit 2. And also they have been pumping seawater into all three of those units. And the seawater is working. What I explained yesterday is if the fuel gets partially uncovered, it’s going to heat up, and when it reaches 2200 degrees, it’ll interact with water to form zirconium and hydrogen. When they release the pressure— and they’ve got to keep the pressure down in order for these pumps to have enough pressure to pump water into the reactor.

So, when they relieve that pressure, which is primarily steam, they’re also releasing some hydrogen, and if there’s enough hydrogen, then the hydrogen will interact with oxygen in the secondary containment building and cause the explosion that we’ve seen in Units 1 and 3.

EM: I see. Do you have any other comments on the current situation?

MM: I do. I sent you a picture earlier this morning that I was hoping you would post instead of another picture of me.

EM: Sure.

MM: For two reasons. I wanted to clarify something that I said in the previous interview [note: in Interviews 1 and 2] where I referred to the building that exploded as the auxiliary building. Not technically correct. It would be correct in a typical pressurized water reactor and also a newer generation boiling water reactor. But in these, these generation boiling water reactors they have a Mark 1 containment structure. And, in fact, the reactor building and the auxiliary building are all combined into one. The correct term with respect to the buildings that have exploded are the “reactor buildings.”

EM: Okay.

MM: And the picture shows kind of the cut-away design of that building. The other reason I wanted to have that picture to talk about is something that really hasn’t been talked about too much in the press. While the containment buildings have held, we also need to keep in mind that outside of the primary containment building— and the secondary containment or reactor building which has been seriously damaged in both Units 1 and 3— is the spent fuel storage pool, where the fuel that had previously been in the reactor has been taken out and is stored longer term until it completely cools. So, one of the considerations that they have is that the heat exchangers and the pumps for the spent fuel pooling cool, pool, excuse me, [spent fuel cooling pool] probably have also not had any power for a significant period of time and could have been damaged in this explosion. And they’re going to have to take steps to make sure that they maintain water in those pools, in these buildings that are now exposed to the environment.

EM: Do you think that they should be providing fresh water to those pools? I know that they’ve been putting seawater into the reactors, and, and from what I’ve heard from you and from what I’ve heard on the news, that’s actually not a very good option because seawater and boron are corrosive. And basically they’re sort of giving up on those plants and saying, “Okay, we’re just trying to keep this from being a nuclear disaster. We’re not actually going to reopen these, these plants. We’re going to have to decommission them.” But in the case of, of a pool where you have long-term storage of nuclear fuel, would it be a problem to add seawater? Would that cause problems later on?

MM: So, the good news is the pools are fairly deep, and they have quite a bit of water over the top of, of the fuel. And it will take some period of time for— assuming the pool is not damaged— for that water to evaporate or boil away.

EM: If they do use saltwater— I mean, these pools from what I understand, they need to have the fuel sitting in them for quite a long time, and, I guess, that’s one of the big problems with nuclear power is what do you do with the spent fuel rods? So what sort of problems might this entail, not just tomorrow or next week, but sort of ten, twenty years in the future for those spent fuel rods? Should there be a problem if they add seawater or no?

MM: I think it’s going to, uh, I think it’s going to depend on the amount of water that’s added and the time before power is restored. Once power is restored and normal cooling and filtration systems can be restored, then they would be able to clean up the water in those pools and get the salinity out of them.

EM: Okay, so it doesn’t sound like that should be a major problem as long as the explosions are not damaging the pools themselves in any way.

MM: It’s a problem, but not, not an immediate problem.

EM: Okay. All right, now I’m going to ask some questions that have been sent in by email or by comments by some people who listened to the first two interviews. And please do continue to send in these comments and questions that you have. I am a graduate student with other obligations, and my dad also has a full-time job, so we may not be able to answer every question, but we will certainly do our best. So, to start off with, the first question was someone wanted me to ask my dad about the contamination that’s being reported by the U.S. Navy, and he wanted to know sort of how far away that is from the plant and he heard something about U.S. Navy sailors requiring some kind of decontamination. Can you speak about that? Do you know anything about that?

MM: No, I don’t know any direct details, only what I’ve seen in the news. And my understanding was that there were some military personnel that had gone inland on a helicopter, and when they returned to the Ronald Reagan [their ship] they were able to detect some radioactive contamination on those folks, and they had to be decontaminated.

EM: Okay. And do you think that— I mean that probably wasn’t any kind of major contamination because, as we’ve discussed the containment units for Fukishima number 1 and 3—although there have been explosions in this outside building, the containment has stayed intact, so there shouldn’t be any kind of major radiation, so this is probably a more minor radiation…

MM: Correct.

EM: …in your opinion or… okay. I just wanted to confirm that; so it’s nothing we should panic about yet, but it is there, and it is a situation that Navy did have to deal with.

MM: So, as we talked about yesterday, that’s one of the indications that to me that they actually have a partial fuel failure in those reactors because of the fact that they were able to detect Cesium and Iodine in the environment. The levels, relatively speaking, will be low. These personnel have been decontaminated, and they should be fine. And the amount of contamination that can be expected probably is a lot dependent on the direction of the winds. Up until now, I think they’ve been relatively lucky that most of the winds have carried the exhaust from the plant out over the ocean. But there will be some found inland, no doubt.

EM: So, clearly the U.S. Navy is testing for this and they’re able to detect this contamination. I don’t know if you can comment on this; I don’t really know anything about it personally. I imagine there must be other people— civilians—who are affected by this as well, and hopefully the Japanese government is making an effort to actually detect that sort of contamination as well.

MM: They are. They’re constantly monitoring, and that’s why they’ve evacuated people in a radius around the plant of 20 kilometers.

EM: Excellent. Okay, a second question that I have was—well, there’s a lot of people who’ve been saying—actually I’ve gotten this from more than one listener—that they want to hear about your worst-case scenario. I don’t know if you want to discuss that; maybe that’s a bit premature?

MM: It’s really hard to speak to what a worst-case scenario would be. I think you mentioned it just in the last part of this interview that the worst-case scenario would be for one of the primary containment structures to fail.

EM: In that case, would we have more… I mean again it’s [crosstalk]

MM: Yeah, I’m sorry. If one of the primary containment structures was to fail then we would have a lot more radiation released to the environment.

As long as they’re able to maintain some water in the reactor vessels and in the containment area, then eventually the fuel that’s in there will cool, but any of the fuel that’s overheated can potentially blister or fail or even melt; and the more that that happens combined if a containment unit was to fail would cause a lot more release of radiation to the environment.

EM: Okay. So a last question that a listener sent in is there has been a study and I’ll post a link[1] to this—I guess it’s not really a study, it’s some thoughts from an MIT scientist who’s an engineer and whose dad worked quite a bit in nuclear power. There’s an article, and it’s been circulating around the internet, and some people asked me what your opinion was on this article, and I wonder if you can just comment on that.

MM: Yeah, I took a look at it and I think there’s a lot of good information there.I think he does a good job of—like we try to do—explain what’s going on.

It’s very difficult, I think, for a member of the public to understand what’s going on because the information is just scattered about in little pieces here or there or, you know, you’re only able to get a sound bite off of the television. So, if there’s somebody that’s really interested [in Fukushima and nuclear power], I would encourage them to go ahead and read that and, I think, combined with these interviews, [it] provides a pretty good picture.

EM: Okay. Thank you so much, Dad! That’s all for today and again, as I said, we both have other obligations so we may not do these interviews every day, but perhaps in a few days we can do a follow-up interview on the situation. And again please do send in any questions that you have. My dad seems happy to answer them. So, thanks, Dad.

MM: Okay, you’re welcome.

EM: Okay, bye.