Update: Thanks to my friend Sophie, there is now a transcript for Interview 8 after the jump.

E: Good morning Dad.

M: Hello, how are you?

E: I’m good.

M: It’s in the(?) afternoon.

E: Oh, is it afteroon? OK. It’s actually afternoon. Well, we’re gonna give the time in a minute. I just wanna first say, my name is Evelyn Mervine and this is an interview with my dad, Mark Mervine, who is a nuclear engineer. This is the 8th in a series of interviews that I’m doing with my dad. If you would like to see the rest of the interviews, either listen to them or-or read the transcripts, for the ones that have transcripts, you can find them on my geology blog, Georneys, which is G-E-O-R-N-E-Y-S, georneys dot blogspot dot com. And I, I would just like to thank, again, all the people who have been transcribing these interviews. There are still a few that have yet to be transcribed, if you have time and interest, and you could transcribe those, I know that would be very useful for those who prefer to read, rather than listen to these interviews. Before we begin, since we are doing many of these interviews, I just want to state that today is March 18th and it is 12:30 PM Eastern Daylight time.

And to start off with, Dad, I would like you to please, um, give an, give us an update about what is happening at Fukushima.

M: OK, again, we’re talking about the Fukushima I nuclear power plant, which consists six reactors. Now, we did a pretty comprehensive update yesterday evening, but I know you had some technical problems posting the files and they just got posted this morning. So, a lot of people probably haven’t had a, had the chance to listen to them. But, um, I’m gonna not go into quite as much detail, so I’m gonna encourage people to at least listen to the first part of, I guess, interview seven?

E: Yes, it’s interview seven.

M: To get a-a pretty comprehensive view of the status. But, anyways, let me jump in and first let me address the-the two plants that are in, um, the least, um, problematic situation and that’s units five and six. Those are the two newest units on the site and they’re physically separated, somewhat, from units one through four. And a couple of days ago, we had reported that they had been able to get a diesel generator started in unit six and that they were attempting to run the equivalent of a long extension cord from unit six to unit five, to be able to get some power back in unit 5. And, in my update last night, I reported that they had been successful, in that and that they were now working on getting cooling systems restored, and waterflow restored in both units five and six.

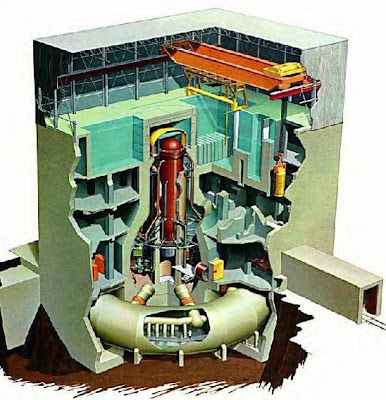

Now, turning our attention to the units that are of the most concern, which are units one, two, three and four. One through three were operating at the time of the earthquake and shut down automatically, and lost power approximately an hour after the earthquake, when the tsunami hit. Unit four had been in the, uh, process of doing a maintenance outage and all of the core for unit four had been offloaded into the spent fuel pool. In the past few days, we’ve seen, uh, a number of escalating problems at these units. And in the case of units one, two and three, uh, based on information that we have and various different releases, it’s confirmed that there is some fuel damage in each one of those three reactors. And also, we’ve had concern about the spent fuel pools at units three and four. One of the things that-that has been a concern, was that, perhaps the primary containment structure around the reactor, itself, might have been damaged in one or more of these units. And the latest reports that I’ve seen indicate that they believe that the primary containments for these three units are still in tact. So, despite some reports, that they may not be, the latest reports are indicating that the three containment units are holding and they’re holding some pressure, so that’s, obviously, good news.

The other good news is the situation with the three reactors has not gotten any worse in the, in the past forty-eight hours. So, they’ve been able to continue pumping, uh, seawater in, venting the steam off to reduce the pressure, which allows more seawater to be pumped in. The cores are not completely covered, but, they do have seawater in there and some cooling is taking place. And the situation is not substantially degrading, uh, on a, on an hourly or daily basis as it seemed that it was, um, uh, early on in this, um, situation, in the past week.

So, some of the bigger concerns that we’ve had, in the past couple of days, have been the loss of water from the unit three and four spent fuel pools and, uh, as a refresher, for everybody, there are seven spent fuel pools at this site, one for each power plant and then one common pool that they can all, um, share, uh, ‘share’ is maybe not a-a good word, but a common pool where fuel rods can be taken and stored. Um, in this, in this seventh pool. And all of the spent fuel pools are of concern. They all need to have water, they all need to have cooling, but three and four have been the most problematic, in that, um, the-they have lost a substantial amount of water and unit four, we believe, uh, lost enough water that, that some of the fuel there was damaged and we’ve discussed, a number of times, what can happen when the zirconium cladding around the fuel reaches a high temperature and causes the formation of hydrogen and we had a hydrogen explosion in unit four and that, since the core has been completely unloaded, that had to have come from the spent fuel pool. And in the past forty-eight hours, they have been trying a number of different methods to get water into those pools. They’ve been trying to use military helicopters to drop water similar to what you would do to stop a forest fire, they have brought in, uh, large water cannon trucks and fire trucks to pour water onto these buildings in the hopes that they can get some of it to go into the spent fuel pools. And they’ve been somewhat successful, but it’s difficult to measure how successful. The reason we know they’re somewhat successful is you can see steam rising, um, especially from unit four, um, after they added this water. So, clearly they were able to get some water, um, onto the fuel.

But there is a concern about the unit four spent fuel pool, in that, um, there was quite a bit of damage to that reactor building when this explosion happened. And it’s, ah, from the photos it looks as if a portion of the concrete wall of the refueling pool has collapsed, but it did look like the fuel liner was intact. Now, the latest reports that I’ve seen today indicate that they, they’re losing more water from that pool than they should based on evaporation rates and they think there might be a small leak, uh, in that pool as well. So, obviously it’s really important that they continue their efforts to drop or pump water into those pools. And I also saw that they’re starting to get concerned about the water level in the unit one spent fuel pool as well.

Now the other, um, news that’s very important is there, it’s taking longer than they had hoped, but they are very close to restoring electrical power to unit two from the grid. And, um, the big change in news, from last night to today, is that they’ve also, they’re also working to, um, to get power back to unit one. And once they’re able to restore power to both units one and two then they’ll be looking, this weekend, to also begin the work to restore power to unit three and four. Now, when power’s restored, that’s a very, very good thing. But, but, we’re not out of the woods. And, in fact, we, with all the damage to all these buildings, we don’t know the status of all of the pumps and valves and heat exchangers that woul-would be needed to restore normal cooling to these units. So, getting electrical power back is the first step, but, there may be quite a bit of challenges and quite a bit of work ahead in order to get pumps working. My hope is, because we have, um, a number of redundancies built in these plants that, at least, we would be able to piece together one workable cooling system in each unit, but, anybody that’s taken a look at the photos that are available on TV or on the internet, you can see with your own eyes the amount of damage that has been a-has been incurred to these reactor buildings due to the hydrogen explosions that have taken place during the past week. So, Evelyn, that’s my current update, um, I just wanna add one thing, before we …

M: turn to questions and that is, Evelyn has had a number of requests for us to, to do interviews for uh-a number of people and, we’re going to have to respectfully decline. We’ll, um, try to answer as many questions as we can, here, but this is taking several hours of our, of our time each day and, uh, we, we just don’t have the time to put, uh, more into it than, than we already are, so, we apologize, but, um, we’ll-we’ll have to confine ourselves to doing these updates and Evelyn has made these freely available. I know they’ve been replicated to many sites around the internet and-and unfortunately, that’s going to have to suffice just-just from a factor of how much time that we have.

E: OK, thank you, Dad. And I’ll echo that as much as we-we want this information out there, we really can’t do more than these interviews but as I, as I said, and if you don’t know this already, um, I encourage you to take these intervies and the transcripts and share them with as many people as possible. Put links on facebook or on your website and (??) and really, really do spread this information, but, as my dad said, unfortunately, this is all that we can commit to, right now.

so, I’m gonna ask a few questions, today, and, again I’ve been receiving many, many emails, um, almost more emails than I really have time to read, so if we miss your question, I’m very sorry. We are trying to answer as many questions as we have time for. SO, to start off with, I’m gonna paraphrase a question from someon who, who’s very concerned about the possible, I guess, sortof, long-lasting effects of radiation on the environment. And, in particular, on the fisheries industry in Japan, because I know that-how Japan does rely quite a bit on the fisheries industry. I know that you’re not a biologist, dad, but could you just comment on that, a little bit?

M: OK, uh, that’s a good question and, uh, anybody that’s watched the, um, news or looked at pictures on the internet, you can see that a number of the towns and villages that have been destroyed a-along the Northwest coast of Japan um, are, um, villages and towns that-that count a lot of the fishing industry. There’s a lot of fishing boats that are stranded on dry land, in these photos, so I think, I think it’s a really good question. Um, I wish I could give a really good answer. But, I-I’m just gonna have to give a general answer because, um, you know I-I don’t have the information as to how much radiation and radio activity has been released and, you know, since the situation is ongoing, we certainly hope that it doesn’t get any worse. I mean, it does appear that in the last 24 hours, or so, that, um, at least the situation is not getting dramatically worse. as it was every day in the past week. But, by no means, are we out of the woods, so, you know, we could have something, um, go wrong or get even worse and have more radiation and radio activity released to the environment, so, we don’t have a complete picture, today. Um, I know that th-th-the Japanese government and they’re being helped by a number of other governments and agencies to-to measure the radiation and radio activity, Will, certainly, as the immediate crisis winds down, make that a priority. Um, obviously, *clears throat* and, I think, I think the mainstream media has-has done a good job of this, of indicating that the, the biggest concern is the area immediately adjacent to the plant. Um, although, we’ve had very good luck on the wind going from the east to the west and, actually, I tihnk a couple days ago, I made a mistake and said west to east. But, in fact, in Japan, they’re very lucky that the wind’s been blowing from the east to the west, which takes a large amount of radiation or (??) radio activity, um, over water, but, since the plant is right on the water, um, you know, more than half of that radio activity is going into the atmosphere above the water and some of it is certainly settling and-and going into the water. Now, as we’ve described, um, it’s a volumetric expansion, so, as we get farther and farther away, the the-the density of radioactivity and any volume that you measure it will be constantly decreasing. And you’ll have the same result in the ocean. So, once this event is finally under control and we’re confident that we’re not going to have any significant additional release of radiation, um, they’ll be able to do samples and they’ll be able to estimate the amount of radioactivity released and be able to give a be-a better estimate. I would, I would say that, you know, for sure, in that, uh, 30 Kilometer, uh, evacuation zone, that, you probably wouldn’t wanna be fishing in that area. But, the farther away you get, the concentration would be so diluted that it probably would have no impact.

So, I know that’s not a very good answer, but it’s the best answer that I think that anybody could give, right now. That, it should definitely be a concern, it should be definitely something that people should be worried about but, um, the farther away you get, the less of a concern it is, and if we can stop the release of radiation, you know, get these plants cooled down and stop the rdiation, then we’ll be able to calculate what actually was, or, probably not calculate, but estimate, how much radiation and radio activity were released. And, um, what the potential impact would be, but, with the exception of that imediate viscinity of the plant and perhaps the water in the immediate viscinity of the plant, um, I don’t, I don’t think there will be a long-term consequence.

E: OK, excellent. Moving on to a second question, this is actually a question from some-from someone in Japan, and before I ask this question, I first want to say that in, I guess over the past couple of days, I have been receiving, um, emails and comments from people who are actually in Japan, many expatriots and even some Japanese people and so that means that this information is reaching Japan and people have said ‘thank you,’ um, and have been, I think those people have been most grateful because they’re right there and they’re dealing with this situation and they say that even in Japan it’s difficult to get information, so, I first wanna say, um, thank you, if you’re listening in Japan, and please pass this on and I hope that this continues to be useful for people and Japan and also elsewhere, in the World. So, I’m just gonna read this question ’cause I think this is maybe a question many people in Japan have, this is from Mike in Tokyo, he says, “Hi, I’m based in Tokyo and I thank you and your dad for all of your hard work. It’s a relief to both my wife and I to get some well-informed perspective on the issue. I wonder if your dad could go into some more detail regarding radiation types that can and cannot be sheilded with clothes and face masks. For example, I understand that workers in close proximity to gamma rays receive no protection with their clothes. On the other hand, people between the 20 KM and 30 KM radius, as instructed by the Japanese government (that’s the evacuation zone), are being instructed to stay inside for protection from radioactive materials in the air. It has also been stated that wearing face masks and body washing after being outside can help remove radioactive material.” Um, and he basically wants you to comment on this and give advice for anybody who isn’t in that area and might be affected by radiation.

M: OK, That’s a very good question and I’m sure one that a lot of people are interested in and, um, what I’m gonna do is give a, uh, um, a partial answer now and, um, I will do a little bit more more homework and w-we’ll address this a little bit more in a follow-up interview. But, there’s, um, generally three types of radiation that we’re concerned with it’s, uh, alpha decay, beta decay and then gamma radiation. So as, as the, um, as this person indicated in their email gamma radiation is primarily only of concern in the immediate viscinity of the plant. Um, and certianly somebody as far away as Tokyo does not have to be concerned about gamma radiation coming from the plant, because, we talked about the advantage of unit five and six being physically separated and um, the farther away you get from a-a gamma ray source, the more that radiation is attenuated and, um, yesterday, I don’t have the days numbered, yesterday evening, they said that the radiation level at the plant boundary was at 1-2 millirem per hour. So, once you get, you know, just a little bit farther away from that, you’re gonna be back down to very low levels of-of radiation. Their concern, for people in Japan is, the, um, particulates also get carried up in the steam and go into the atmosphere from either the venting of the reactors or from the spent fuel pools. And their, um, definitely, a concern. And the biggest concern you have is breathing in, uh, these particulates, because, um, in the case of, uh, alpha uh, radioactivity or decay, um, it, the, uh, it has a very low penetrating ability. So, normally, your skin, or certainly your clothing would, would stop that from being a concern. But if you breathe it in, it is a concern, and that’s why I mentioned I think it, I don’t know if it was yesterday or the day before, that in here, in the US, it’s very common when you buy a house to have it tested for radon. Uh, radon is a naturally occurring, uh, radioactivity from the rocks and the ground here, in the US, and it’s-it’s gaseous, so the concern is you breathe it in and, and if you breathe in, um, material containing alpha particles, um, it has a different effect because then you don’t have your skin or your clothes to protect you, even though it only penetrates a small distance, it’s going right inside your body. And to a similar extent, um, you have to worry about beta particulates, they will penetrate a little bit farther, but, again, the bigger concern is, uh, inhalation. So, for the, for the most part, uh, normal clothing, uh, face masks, will make a big difference if there are elevated levels of radioactive particulates in the atmosphere.

Again, I’d like to ephasize, at this point, that there’s no indication that there’s any concern, um, that the radioactivity levels in Tokyo have risen above normal background levels, but the levels they’re at there’s no concern and there should be no panic at this point. I encourage people to, you know follow the directions of the government and not panic or not be overly concerned. But, in the event that the situation got worse and the wind shifted it and there was a concern, um, the concern would be mostly from the particulates that are in the atmosphere and there are very good ways to protect yourself from that. And that’s why, oftentimes you’ll hear a request from the government rather to evacuate that you should shelter in place and you should seal all your doors and windows. Because, if you do that, then it’s not gonna get in your house, and if it doesn’t get in your house, you won’t get it on you, you won’t be able to breathe it in, or, at least, it will minimize it, no house, obviously, is completely air-tight, but, um, it will definitely minimize it. So, like I said, I’ll do a little bit more homework and try to give a little bit, uh, better overview of that in a subsequent interview, but, ah, right now, you know, outside of-of the evacuation areas, um, the levels are not such that there should be a concern for human health. And, certianly, um, all the way to Tokyo, there, there’s no concern, at the moment.

E: Thanks, Dad. I’m gonna go on to another question, and this one comes from Alberto, who’s actually in Chile and he asks a very good question he says, “I have one question, giving your father’s knowledge. Chile, a country in South America, as you might know, was devastated with an earthquake and a tsunami last year of somewhat similar intensity. Today, the Chile is evaluating the construction of nuclear plants and since this disaster struck in Japan, many citizens are fearing something similar could occur if one was built. knowing that, the question would be, how are the newer designs, existing today, better equipped to handle both an earthquake and a tsunami of this scale or bigger and would your father consider it dangerous to build them in a place such as Chile. Um, please remember that the biggest earthquake registered in the World was registered in Chile some 50 years ago.

M: OK, so that’s a good question, not just for people in Chile, but, I think, all over the World, because there are fault lines and earthquakes of different magnetudes all over the world. And, I-I think we actually talked about this in one of the interviews, already, but, um, so, you know, typically, typical way that this is done, when a nuclear power plant is built, is that there’s a requirement based on worst case scenario for an earthquake for the plant to be built to withstand that. And, um, here, in the US, I’ve gone to plants that are relatively stable areas and worked in some of those, I’ve gone to plants that are in more active areas. And the difference in the construction of the plants is, um, very interesting, actually. The plants that are in the more, uh, geographic, uh, sorry …

E: Geological, dad, this is my field now.

M: Geological, thank you,

(they laugh)

M: Um, areas, have to have a lot more supports for the piping, they use a lot of hydrolic dampers, which will allow things to move without breaking, um, there may be, uh, expansion-height systems built so that, uh, systems can, can move, uh, without breaking. So there’s a lot of different design requirements, and then, of course, things have to be built stronger so you might have to use more steel reinforcement in your concrete, uh, and those type of things, when you look at, at building a plant. Or, really, um, any structure. So, for instance, uh, in-in Tokyo the requirements for the building, uh, for the construction of a building are much more rigorous than they would be in another country that may only expect to have an of two or three on the richter scale. An-and the way they do that is the foundations are sunk much deeper, they normally need to go to bedrock. Um, they use a lot more concrete, a lot more steel reinforcements. Um, so, uh, obviously you have to go to more of an extent at a nuclear power plant, but, um, all buildings, you know, have to have, um, adaptations for when you’re in an area that is more prone to earthquakes than, uh, than another. Now, with respect to some of the newer designs, um, I think, I think it’s a good question. And, what I promise to do, is, is do a little bit of homework, because, my information would be a little bit out of date, since I haven’t been, actually been active in the industry for a few years. Um, and, and I know the designs have been updated substantially in the past few years. if I do a little homework, and I come back to this audience and give them a little perspective of some of the design changes that are being (??) into the new design for if you were to build a power plant now, versus, the plants that were built, um, in the 60s 70s and 80s.

E: OK, so we’ll return to that question.

M: Yeah, I’ll come back to that question, I mean i-in generality there’s been a lot of improvements. The designs have been simplified, there’s a lot more passive systems that don’t require, uh, operator intervention, that don’t require pumps. I know that some of the designs used, you know, significantly fewer, uh, moving pieces. Significantly fewer pumps, significantly fewer valves and, of course, the simpler you can make it, and, and, the more, uh, you can rely on the principles of, uh, passive cooling and those types of things, uh, the better you are, as evidenced by what we’ve seen in the past week. But, let me do a little bit of homework and come back some more up-to-date details for people.

E: Sounds great, dad. The last question that we have time for, today, this question is actually coming from several people, and I think that this is because, um, many people have seen this and been concerned by it, basically, there has been some footage that has been released to the general public from one of the helicopters that was dropping water on, I-I presume it was the pool, uh, the spent fuel rod pool at reactor number four. And, I think, um, people were, were quite shocked, um, when they saw this video, just at the extent of the damage and people wanted to know if you could comment on that, and also, if you learned anything new from that video that you didn’t know, already.

M: Well, I think that’s a good question, and, I think I had actually commented that, yesterday or the day before, that I’d finally gotten to see some close-up pictures of the damage and I was, uh, pretty surprised at what I saw. We were told, originally, that there’d been a hydrogen explosion in unit four and a couple of 8 ft. by 8 ft. square panels had been knocked out. But, when we saw the photos with our own eyes, we saw massive a-amounts of damage to the-the unit four reactor building. Um, and, if you, um, look at the photos you can see that there’s some fairly substantial amounts of damage to the units one, three and four reactor buildings. And, then, some of the questions that people have asked, we address that in some of our interviews, people asked about would it be possible to move the fuel and we said, well, because of the damage to the reactor building, no, because all the equipment that would be used to, to move it would be des-would be, would have beend damaged. And, I think my concern, which is shared by, by other people, um, I think, again, the main (??) media’s trying to do a better job, the soundbytes are a little bit longer, they’ve had a few more true experts, um, that they’ve been talking to. Have addressed concerns that it’s great that we’re gonna be getting power back, absolutely is a huge, huge step forward, but, given the photographs, given the amount of damage, given the radiation levels, it’s gonna be a long and difficult journey to get enough pumps and valves and heat exchangers functioning to truely cool these plants down and put them in a safe state. And, I think that’s a thing that concerns me the most about the photographs, is, um, how much, how much damage is there below what we can see. Because the, the systems that they’re gonna need to restore, in order to cool these reactors, would have been a couple levels down from what we can see in the photographs, so, my sincere hope is that the-the damage we see confined to what we can see and that, below that, there’s less damage. So, um, it is, um, pretty amazing to see those photographs, I must admit. And, the biggest concern about the damage that we see in those photographs is the concern for the spent fuel pools, which are in that rubble, uh, of those three reactors.

E: OK, uh, well that’s quite sobering to hear, but, thank you for commenting on that, Dad. Before we end, I just wanna say, I have been receiving so many emails and questions, please do keep sending those in. At first, I was replying to every person and then saying ‘thank you,’ um, if I don’t reply to you, I’m sorry, a-at this point, I’m just receiving so many emails that I-I can’t reply to every single one, but, but I do appreciate them, and, um, I am planning on going through all of them and showing them to my dad, at some point, so please do keep sending in your, your comments and your-your questions, um, we will look at them, and, um, we do appreciate them. That’s all, do you have anything else, Dad, before we end?

M: I don’t, I, again, I hope that this is helping people. I-I do wish that, you know, we could accomodate all the questions, and, um, all the requests that-that folks have had to talk with them, but they’re just, there isn’t enough time in the day, um, we’re each putting somewhere between three or four hours into this every day, in order to do the homework and-and be able to, um, maintain the site, and-and post these interviews. And, uh, both of us are also trying to do our day jobs, as well, so, um, we’ll keep doing it as long as we can and as long as there’s a need, but, um, again, apologies that we can’t respond to everybody.

E: Alright, thanks very much, dad, I’m gonna go try and get this posted right away.

M: OK, thank you.