At long last, I’m finishing up my series of posts about my October 2013 visit to the small town of Sutherland in South Africa’s Northern Cape province. Sutherland is home to a South African Astronomical Observatory (SAAO) research station that contains many telescopes, including the Southern African Large Telescope (SALT). You can read Part I of this series here, Part II of this series here, Part III of this series here, Part IV of this series here, and Part V of this series here. In my previous posts, I blogged about the astronomical observatory. In the last couple of posts, I’d like to blog about some of the geology that I observed on the drive from Cape Town to Sutherland.

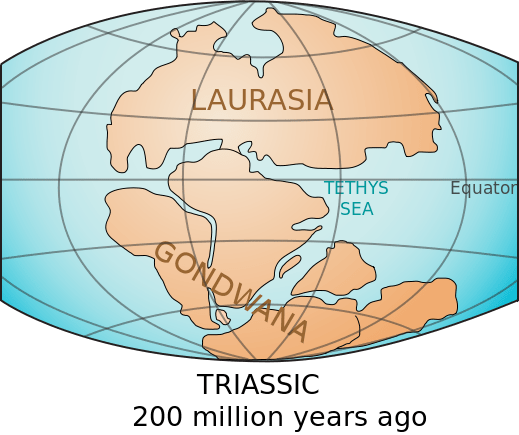

On the drive to Sutherland, we stopped at some fantastic roadcut exposures of Dwyka Group glacial sedimentary rock. Specifically, we stopped to look at some Dwyka diamictite, a term used to describe a poorly sorted sedimentary rock, commonly one deposited by a glacier. Dwyka glacial sediments are often referred to as “Dwyka tillite”. However, tillite is a specific term that refers to poorly-sorted sediments deposited directly underneath a glacier. Since there is evidence that many of the Dwyka glacial sediments were deposited in a glaciomarine environment, the term “Dwyka diamictite” is more accurate… and also has pleasing alliteration! Dwyka diamictite is Carboniferous in age and was left behind by a large glacier that covered southern Gondwana. Thus, Dwyka diamictite can be found on several continents and provides evidence that the supercontinent of Gondwana once existed.

Dwyka diamictite can easily be recognized from a distance by its distinctive “tombstone” appearance:

For some reason (perhaps one of my geomorphologist readers knows why?), the Dwyka tends to weather into “tombstone” shapes.

Dwyka diamictite is generally is covered in a reddish-brown oxidation rim. A fresh surface of Dwyka consists of a dark gray matrix (finer-grained glacial sediment) that contains clasts of all sizes, shapes, and rock types.

Here’s a look at a fresh roadcut surface of Dwyka diamictite:

I was really excited to take a look at such a beautiful roadcut of Dwyka diamictite:

Here are some pictures of some of the interesting clasts I saw in the Dwyka diamictite outcrop:

How many of the above clasts can you identify? I see some igneous rocks, some sedimentary rocks, some metamorphic rocks… all sorts of rocks!

Well, that’s all for this “Sutherland Sky” post. Next I’ll share some pictures of some rocks I saw as we drove through the Cape Fold Belt on our way from Cape Town to Sutherland.