For those of you who have not yet heard, there has recently been an enormous Magnitude 8.9 earthquake and an accompanying tsunami in Japan. There are currently tsunami warnings for the Pacific, so if you live on the West coast of the US or anywhere in the Pacific Ocean, please be cautious. The USGS (US Geological Survey) tsunami warning for the US can be found here.

Below is a map of estimated tsunami travel times. CNN has converted these to Pacific Standard Time estimates.

|

| Estimated tsunami travel times. Figure taken from NOAA here. Click to view larger. Note there is an error in this figure: the star is in the wrong place. The earthquake actually occurred farther north, where the waves originate. |

My fellow geobloggers are currently doing a great job of covering the recent news of the Japan earthquake. Callan Bentley over at Mountain Beltway has a good summary of earthquake coverage.

Here are a few more geoblogs & websites discussing the Japanese earthquake. I’ll update this list as I find more good sites:

Geoblogs:

Mountain Beltway

Dan’s Wild Science Journal

Paleoseismicity

Geotripper

Highly Allochthonous

Other Websites:

USGS

NOAA’s West Coast and Alaska Tsunami Warning Center

NOAA’s Pacific Tsunami Warning Center

Since I have quite a few non-geologist readers, I thought I would quickly discuss why Japan is such an earthshaking place with so many earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanoes. While the gigantic 8.9 magnitude earthquake is impressive even for Japan, this is a part of the planet where geologists expect large and frequent earthquakes. Historically, there has been quite a bit of earthshaking in the area of Japan where the recent, enormous earthquake originated.

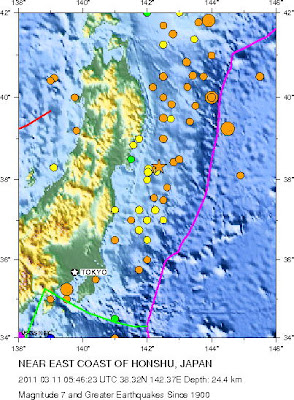

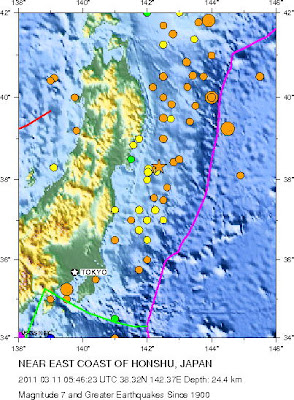

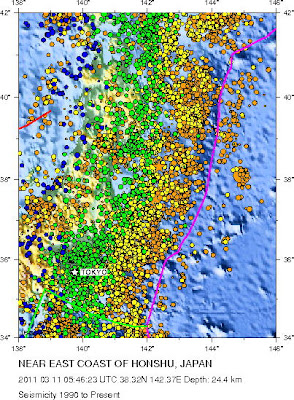

Here are a few historical maps from the USGS showing seismicity (aka earthshaking) in the area where the recent Japan earthquake originated. The location of the recent earthquake is given as an orange star:

|

| Figure taken from USGS here. Click to view larger. |

|

|

|

|

| Figure taken from USGS here. Click to view larger. |

The first figure shows that there have been many large (greater than magnitude 7) and shallow (meaning more destructive at Earth’s surface) earthquakes in this area of Japan since 1900. The second figure shows that there has been quite a bit of earthshaking- both small and large- in this area of Japan since 1990.

Why is there so much earthshaking in Japan? Simply put, there is so much earthshaking in Japan because the Japanese islands are part of a volcanic island arc. As a quick reminder for those of you who are a little rusty on Geology 101, a volcanic island arc is a place where volcanoes are produced above a subduction zone. A subduction zone is a place where one tectonic plate is going underneath (aka subducting) another tectonic plate.

Here are a couple of images showing subduction:

|

| Volcanic island arc & subduction zone. Figure taken from here. Click to view larger. |

|

| Artistic (not quite scientifically accurate but very pretty) depiction of an island arc & subduction zone. Image taken from here. Click to view larger. |

When an oceanic plate subducts underneath a continental plate, this produces volcanism on the continent, such as the volcanism that occurs in the Western US in the Cascades. When an oceanic plate subducts underneath another oceanic plate, a volcanic island arc is formed. There is no land originally, but a chain of island arcs builds up as volcanism develops above the subduction zone.

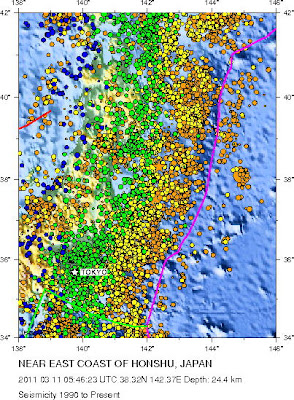

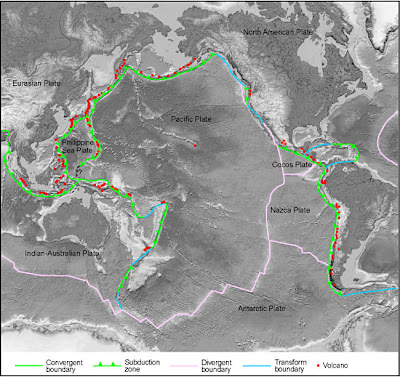

Here is a figure showing that Japan is part of a greater subduction zone called the Pacific “Ring of Fire”:

|

| Plate boundaries, subduction zones, and volcanoes in the Pacific “Ring of Fire.” Figure taken from here. Click to view larger. |

But why is there volcanism above a subduction zone? Well, this relates to a fundamental concept in geology- why do rocks melt?

A common misconception is that rocks melt because they are heated. Actually, most of the time rocks do not melt because they become hotter. Think about it- the interior of the Earth is very hot, much hotter than the shallow Earth where melts feeding volcanoes are generated. Yet, the interior of the Earth is pretty much all solid, except for the outer core. The reason that the interior of the Earth is not all melted, even though it is very hot, is because there is also an enormous amount of pressure in the interior of the Earth. So, when thinking about whether or not a rock will become molten, you need to think about both temperature and pressure.

Most rocks on Earth actually melt because of a sudden change in pressure. Geologists often talk about fancy shmancy “adiabatic decompression melting” occurring at mid-ocean ridges. To translate this into everyday language, “adiabatic decompression melting” just means that melting occurs because rock is moved quickly upward in the Earth. Rocks tend to lose heat very slowly, so if they are brought upwards quickly enough they won’t have time to cool down. They remain hot, but because they are brought up to a more shallow part of the Earth, they have less confining pressure and are able to melt. To breakdown the previous phrase: adiabatic = no heat loss, decompression = less pressure, and melting = solid to liquid.

So, at mid-ocean ridges- places where tectonic plates move apart and rocks are able to move upwards quickly- rocks melt because of adiabatic decompression melting. Now that you understand what that means, you have a great science phrase to impress your friends with at that next party.

But what about subduction zones, places where plates converge? The mantle melts at subduction zones because of the addition of volatiles, such as water and carbon dioxide. It turns out, if you add water, carbon dioxide, or another volatile to a rock, it will melt at a much lower temperature than normal. To put it simply, the large volatiles sort of interrupt the normal chemical bonds in the rock and make it easier to break apart that rock and turn it from solid to liquid. At a subduction zone, a plate (usually an oceanic plate) is going deep into the Earth. When this plate subducts, it brings volatiles with it into the mantle– for instance, water stored in deep-sea sediments. When the subducting plate is heated as it plunges into the hot, deep mantle, these volatiles are released and travel upwards since they are buoyant. The volatiles lower the melting temperature of the rock above the subducting plate and this rock melts, forming volcanoes above the subduction zone.

The wonderful diagram below (from Wikipedia Commons) explains how melts are produced in the Earth. The geotherm is the rate at which the temperature changes with depth in the Earth. The solidus is the line below which the mantle is solid. Above this line, the mantle starts to melt. When the geotherm crosses the solidus, melts are produced.

In the normal case, the solidus and the geotherm do not cross and no melting (and thus no volcanism) is produced. When plates diverge, mantle material rises and decompresses- the mantle melts because it encounters a lower pressure. When plates converge and subduction occurs, the subducting plate releases volatiles (such as water and carbon dioxide) and these volatiles lower the solidus temperature and the mantle melts. At hotspots, the geotherm is higher (by about 100-200 degrees C) and melting is able to occur.

|

| Excellent diagram showing the three ways that melts are produced on Earth. Click to view larger. From Wikipedia Commons here. |

Finally, why do earthquakes occur at subduction zones such as Japan? Well, any place where tectonic plates move past one another will occasionally experience earthshaking. Earthquakes occur where plates move apart (such as at mid-ocean ridges), slide past each other (such as at the San Andreas fault), or converge and subduct (such as at Japan). The movement of the plates- especially if sudden- has the potential to create very large earthquakes. Something that is unique about subduction plate boundaries (relative to convergent and transform- or sliding- plate boundaries) is that there can be very deep earthquakes.

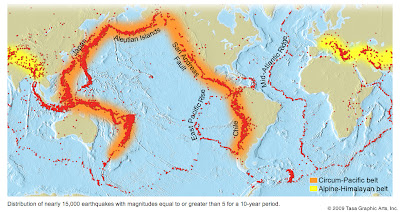

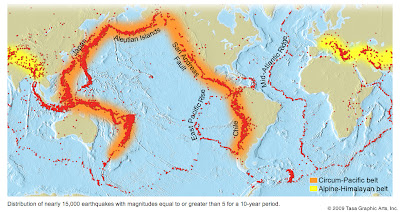

Here is a comparison of earthquakes and tectonic plate boundaries:

|

| Worldwide earthquake distribution. Figure from Tasa Graphics. Click to view larger. |

|

| Worldwide Plate Boundaries. Figure from Tasa Graphics. The little triangles indicate a subduction zone boundary. Click to view larger. |

|

|

|

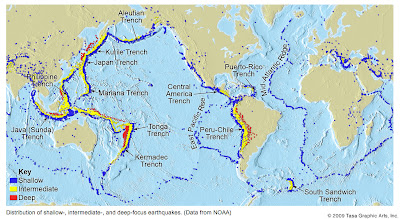

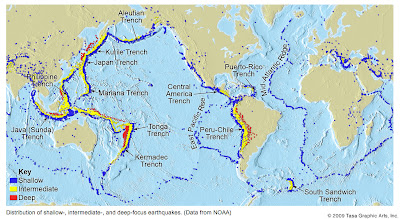

Notice how deep earthquakes occur at subduction zones:

|

| Worldwide distribution of earthquake depth. Figure from Tasa Graphics. Click to view larger. |

|

|

| Depth of earthquakes at a subduction zone. Figure taken from here. Click to view larger. |

Finally, below is a figure showing why Japan is an especially tumultuous region of plate convergence. Near the recent earthquake location, three tectonic plates are interacting! The interaction of these three plates makes large earthquakes, such as the recent 8.9 magnitude one, a likely occurrence.

|

| Three tectonic plates in Japan. Figure taken from here. Click to view larger. |