|

| Coquina rock. Image taken from wikipedia here. |

def. Coquina (“co-keen-ah”):

A sedimentary rock consisting of loosely-consolidated fragments of shells and/or coral. The matrix or “cement” consolidating the fragments is generally calcium carbonate or phosphate. Coquina is a soft, white rock which is often used as a building stone. Coquina forms in near-shore environments, such as marine reefs. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, coquina is a loanword from Spanish meaning “shell-fish” or “cockle” (a type of bivalve mollusc). Also according to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word was first used in English (to refer to the building stone) in 1837 in the book The Territory of Florida by J.L. Williams.

I remember exactly when I first learned the word “coquina.” When I was in high school, I had the opportunity to take some science electives in addition to the normal biology, chemistry, and physics courses. One of the electives I took was geology. I remember reading the textbook for the class (I believe it was Essentials of Geology), and there was a picture of coquina rock in the chapter on sedimentary rocks. I remember thinking, “Cool!” when I saw the picture of coquina. To me, coquina was a great rock because it was so simple: the rock was clearly composed of shell and coral fragments which had been cemented together. The fragments were large and obvious and just barely cemented together. I think I liked coquina so much because I was a bit overwhelmed by all of the rock and mineral types when I took that first high school geology class. I loved learning about rocks and minerals, but I found myself somewhat befuddled by all of the names and strategies used for identification. I had to think before I could confidently distinguish amphibole from pyroxene or diorite from dolerite. Coquina, on the other hand, was a refreshingly simple rock to identify.

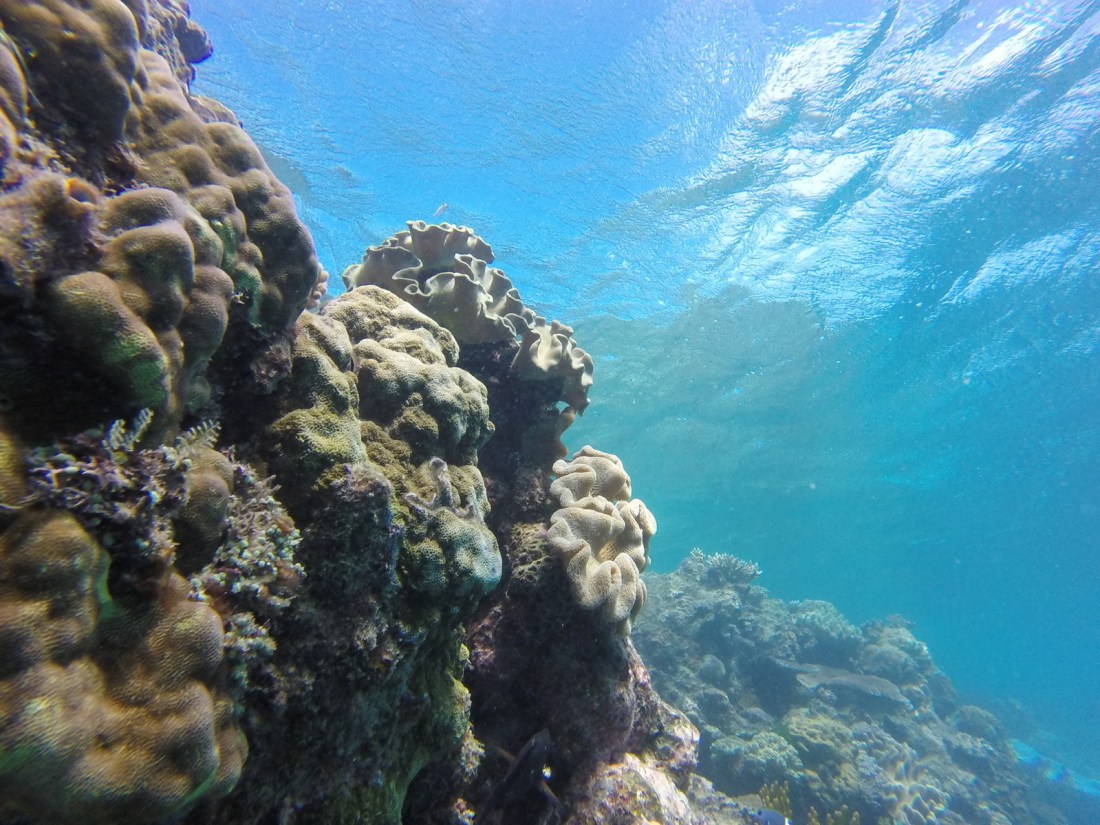

While relatively simple to identify, coquina can actually be a complex rock. There are many different types of shell and coral fragments that can cement together to form coquina. Identification of these fragments is important in order to fully classify and understand the origin of a particular coquina, but this identification can sometimes be challenging. Like with any sedimentary rock, the origin of a particular fragment in coquina may sometimes be mysterious. Coquina may also be covered in mud and dirt or weathered, making identification difficult at first glance. Many coquina rocks were formed recently (within the past few thousand years), but some coquina rocks are older. Determining the age of older coquina is sometimes important for understanding local geology. For instance, since coquina forms in a near-shore environment, determining ages of coquina deposits (either marine or on land) can help reconstruct sea level rise and fall over time. However, determining the ages of sedimentary rocks, including coquina, is always a challenge since diverse fragments (often of different ages) have come together to form new rock.

Below is a picture some coquina that was collected from the seafloor just off the coast of southern Africa by my fiance, who is also a geologist. My fiance regularly finds coquina and shell fragments in the marine sedimentary rocks he studies. He is sometimes able to date coquina and other shell-containing sedimentary rocks by identification of shells. Since certain shell-making organisms lived at specific times in the past, identification of some types of shells can be used to date coquina rocks. Coquina rocks can also sometimes be dated by their location within a sequence of sedimentary rocks. For instance, if the ages of rock layers on either side of a coquina layer are of a known age, then the age of the coquina layer can be bracketed.

My fiance writes about this particular coquina,

Here is a picture of the coquina rocks – bear in mind these were photographed right after being collected off the sea-bed so are still covered in bits of mud. The entire “rock” consists of shell cemented by calcareous material and phosphorite. The sample contains least two different species of shell: a thin, long, spirally shell and a clam-like shell. From my seismic work I’ve interpreted this unit as Miocene in age (Burdigalian ~ 20 million years old).

|

Coquina collected at sea off the coast of Southern Africa.

Photo courtesy of Jackie Gauntlett. |

Coquina is commonly used as a building stone, particularly in places (such as Florida and the West Indies) with large coquina deposits. Coquina is a very soft building material, so soft that it needs to be dried out in the sun for a few years before being used as a building stone. Apparently, the softness of coquina made it an ideal building stone for some forts. For example, coquina was used to build the Castillo de San Marcos Fort in St. Augustine, Florida. The fort was built by the Spanish in the late 1600s when Florida was a Spanish territory. When British forces attacked the fort in 1702 during the Siege of St. Augustine, they fired cannon balls at the fort. However, the cannons were not effective at destroying the fort because the cannonballs kept sinking into the soft coquina. Forts are normally made out of harder stone, which fractures or punctures when hit with cannonballs.

Since the British could not break through the coquina walls, they were forced to lay siege to the fort. Eventually, Spanish relief ships forced the British to withdraw. The British managed to burn down much of the St. Augustine fort as they retreated (not sure why they didn’t try that earlier, honestly), but the fort was rebuilt and refurbished by the Spanish a few years later. However, the British did not give up, returning for a second siege and eventually taking over the fort in 1763. Just think, though… that pesky soft coquina kept the British from taking over the fort for 61 years.

|

| Castillo de San Marcos fort. Image taken from wikipedia here. |

In addition to being a good cannonball protector, coquina is a beautiful ornamental building stone. In response to my request on twitter (@GeoEvelyn) for coquina pictures, Phoebe Cohen (@PhoebeFossil) sent me some beautiful coquina pictures which she took just a couple of days ago in Shark Bay, Australia. The building where she is currently staying is made out of gorgeous coquina that was mined locally.

Phoebe writes,

This building at Carbla Station, Western Australia, is made entirely of blocks of coquina. The coquina comes from the nearby beach of Shark Bay, a hyper-saline semi-restricted area. The coquina forms right near the beach, mainly from tiny clam shells washed up onshore. The shells are compressed and turned into a cohesive mass as rain water filters through them, dissolving a little bit of the shell’s calcium carbonate, which then glues the shells together. The coquina here is no longer used for building stone, as it is now in a protected marine park area.

Here are Phoebe’s pictures of the coquina building:

|

| Coquina building in Shark Bay, Australia. Photo courtesy of Phoebe Cohen. |

|

A closer look at the coquina building stones, Shark Bay, Australia.

Photo courtesy of Phoebe Cohen. |

|

An even closer look at a coquina building stone in Shark Bay, Australia.

Photo courtesy of Phoebe Cohen. |

And here’s a picture from Phoebe of an old coquina mining site:

|

Old coquina mining location, Carbla Beach, Shark Bay, Australia.

Photo courtesy of Phoebe Cohen. |